How Projective Tests Are Used to Measure Personality

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Projective tests in psychology are assessment tools that present individuals with ambiguous stimuli, prompting them to interpret or create stories about them. Common examples include the Rorschach inkblot and Thematic Apperception tests (TAT).

The idea behind projective tests is that when individuals are presented with ambiguous stimuli, such as pictures or inkblots, they will project their unconscious feelings, thoughts, and desires onto their interpretations of these stimuli. By analyzing these responses, psychologists aim to gain insight into the individual’s social behavior, thoughts, emotions, and potential internal conflicts.

The responses reveal underlying emotions, desires, and conflicts, based on the idea that people project their unconscious feelings onto ambiguous stimuli.

The seminal works on the “projective hypothesis” were proposed by Murray (1938) and Frank (1939). They suggested that allowing free-form responses to ambiguous or “culture-free” stimuli would encourage the emergence of personal meanings, feelings, and other implicit processes that may be resistant to conscious efforts at misrepresentation.

Labeling certain assessment techniques as “projective” provided a clever conceptual contrast to more “objective” measures, such as rating scales that restrict the range of acceptable responses.

Some prototypical features of projective instruments include:

- The test stimuli incorporate some degree of ambiguity – for example, the Rorschach inkblots elicit the question “What might this be?” and the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) requires crafting stories based on pictures of people engaged in unclear behavior.

- While some responses violate the instructions (e.g., refusing to respond), the number of acceptable responses is essentially infinite. Traditional Rorschach administration allowed the respondent to decide how many responses to give, though the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS) now limits this to four responses per card.

- The ambiguity is intended to provoke idiosyncratic patterns of responding, such as unusual perceptual interpretations or justifications on the Rorschach or atypical story content or structure on the TAT.

- The free-response format often necessitates individualized administration and specialized training in giving instructions, scoring, and interpretation.

Thematic Apperception Test

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) is a projective psychological test wherein individuals view ambiguous pictures and then create stories about them.

By analyzing the narratives, psychologists aim to gain insight into the individual’s emotions, inner conflicts, and interpersonal dynamics, as it’s believed that personal experiences and underlying feelings influence the created stories.

The thematic apperception test taps into a person’s unconscious mind to reveal the repressed aspects of their personality.

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) cards are primarily designed for individuals aged 14 and older. However, there are variations of the test, like the Children’s Apperception Test (CAT), specifically tailored for children aged 3 to 10 years. The selection of cards and interpretation are adjusted based on the age and developmental level of the individual.

Although the picture, illustration, drawing, or cartoon used must be interesting enough to encourage discussion, it should be vague enough not to immediately give away what the project is about.

TAT can be used in various ways, from eliciting qualities associated with different products to perceptions about the kind of people who might use certain products or services.

The examiner presents a selection of TAT cards one by one. While there are 31 cards in a standard TAT deck, usually only 10-12 are selected for a single session, based on the individual’s age, gender, and other factors.

For each card, the individual creates and tells a story based on the image. The examiner typically remains passive, allowing the individual to provide their narrative without interruption. If the individual is hesitant, the examiner might prompt or encourage elaboration.

The person must look at the picture(s) and tell a story. For example:

What has led up to the event shown What is happening at the moment What the characters are thinking and feeling What the outcome of the story was

Once all the stories are told, the examiner may ask follow-up questions to clarify certain points or explore parts of the narratives in more depth.

How do you interpret a TAT test?

After the test, the examiner reviews the narratives, analyzing them for themes, conflicts, emotions, interpersonal dynamics, and other relevant psychological insights. The TAT’s results are then often integrated with other assessment data to form a comprehensive psychological profile.

It’s important to note that TAT interpretation is subjective, and there can be variability in interpretations.

The skill of the psychologist, their familiarity with the test, and their understanding of the individual all play crucial roles in the interpretation process.

- Story Content : The psychologist examines the narratives for common themes, conflicts, characters, and resolutions.

- Emotional Responses : The expressed emotions, anxieties, and feelings in the stories are noted.

- Interpersonal Dynamics : Relationships between characters can provide insight into the individual’s interpersonal relationships and their view of social dynamics.

- Projection : Since TAT is a projective test, personal experiences, desires, fears, and conflicts are believed to be projected onto the characters and events of the stories.

- Consistency : Patterns in responses across multiple cards can provide robust insights into persistent themes or concerns in an individual’s life.

- Comparison to Norms : While TAT doesn’t have strict “norms” like some other tests, experienced psychologists often use their knowledge of typical responses to gauge the uniqueness or concern of a particular narrative.

- Integration with Other Information : The TAT results are often integrated with other clinical data, interviews, and assessments to form a comprehensive understanding of the individual.

Draw a Person Test

The Draw A Person Test, often abbreviated as DAP, is a projective psychological assessment that asks an individual to draw a person.

It’s used to evaluate cognitive development in children and, in some interpretations, to gain insights into an individual’s personality, emotions, or potential psychological disorders. The drawn figures are analyzed based on various criteria, including detail, proportion, and presence or omission of features.

Figure drawings are projective diagnostic techniques in which an individual is instructed to draw a person, object, or situation to assess cognitive, interpersonal, or psychological functioning.

The test can be used to evaluate children and adolescents for various purposes (e.g. self-image , family relationships, cognitive ability, and personality).

In most cases, figure-drawing tests are given to children. This is because it is a simple, manageable task that children can relate to and enjoy.

The child is instructed to draw a picture of a person. Sometimes, further instructions are given, such as drawing a man, a woman, and themselves on separate sheets. This can allow for a more varied assessment.

After the drawing is completed, the examiner may ask the individual about the drawing. Open-ended questions can include:

- Who is the person in the drawing?

- What is the person doing?

- What might the person be thinking or feeling?

- “What kind of day is this person having?”

Questions might be posed to understand the emotions behind certain elements of the drawing: “How does this person feel about what’s happening?”

If the drawing has ambiguous or unclear elements, the examiner might ask about them, e.g., “I’m curious about this over here, can you explain it?”

Interpretation

The examiner evaluates the drawing based on a variety of criteria. This can include the size of the drawing, the placement on the page, the presence or omission of body parts, the level of detail, and other aspects. For some standardized versions of the DAP, scoring systems are in place, but interpretations can still be subjective.

It’s essential to approach the analysis with caution. While these interpretations can offer insights, they are not definitive diagnoses. Individual and cultural differences, as well as context, play a crucial role in understanding the meaning behind the drawings.

- Body Proportions : The size and proportion of the drawn figure can be indicative of self-perception and self-esteem. A tiny figure might indicate feelings of insignificance or insecurity, while an overly large one might hint at inflated self-importance.

- Omissions : Missing body parts (like hands, feet, or ears) can be significant. For example, omission of hands might be linked to feelings of helplessness, though interpretations can vary.

- Placement on the Page : A figure drawn in the corner might suggest feelings of isolation or marginalization, whereas central placement might indicate a balanced self-concept.

- Detail Level : An excessive amount of detail or focus on specific body parts can indicate fixation or heightened significance. Conversely, lack of detail might suggest avoidance or neglect.

- Sequencing : If multiple figures are drawn, the sequence or order of the drawings might offer insights. For instance, drawing oneself last could hint at self-neglect or prioritizing others.

- Interactions : The interactions (or lack thereof) between figures, if multiple are drawn, can indicate interpersonal dynamics or feelings of connectivity or isolation.

Some figure-drawing tests are primarily measures of cognitive abilities or cognitive development. In these tests, there is a consideration of how well a child draws and the content of a child’s drawing. In some tests, the child’s self-image is considered through the drawings.

The Draw-a-Person: QSS (Quantitative Scoring System) is a standardized version of the Draw-A-Person test developed to assess intellectual functioning, primarily in children. It uses objective criteria and a scoring system to evaluate the drawings to estimate cognitive abilities.

In other figure-drawing tests, interpersonal relationships are assessed by having the child draw a family or some other situation in which more than one person is present.

Some tests are used for the evaluation of child abuse. Other tests involve personality interpretation through drawings of objects, such as a tree or a house, as well as people.

Finally, some figure drawing tests are used as part of the diagnostic procedure for specific psychological or neuropsychological impairment types, such as central nervous system dysfunction or mental retardation.

The House-Tree-Person (HTP) test (Buck, 1948) provides a measure of self-perception and attitudes by requiring the test taker to draw a house, a tree, and a person.

- The picture of the house is supposed to conjure the child’s feelings toward his or her family.

- The picture of the tree is supposed to elicit feelings of strength or weakness. The picture of the person, as with other figure drawing tests, elicits information regarding the child’s self-concept.

The HTP, though mostly given to children and adolescents, is appropriate for anyone over the age of three.

Rorschach Inkblot Test

The Rorschach Inkblot Test is a projective psychological test developed in 1921 by Hermann Rorschach (Rorschach, 1921).

It consists of 10 symmetrical inkblots – 5 are black and white, 2 are black/red/gray, and 3 are multicolored (Exner, 2003).

During the test, the respondent is shown each card and asked, “What might this be?” (Meyer & Mihura, 2020).

The respondent verbalizes what they see in each inkblot within a set time limit. The tester then clarifies the response in an inquiry phase to understand what aspects of the blot elicited the response (Meyer et al., 2011).

Steps are taken to ensure standardized administration procedures and to facilitate coding reliability.

A respondent’s reactions to the ambiguous inkblots are analyzed in terms of location, determinants, content, popularity, and other codes to derive scores on variables related to coping style, affect regulation, information processing, self-perception, and more (Mihura et al., 2013; Weiner, 1994).

These scores contribute to interpreting perceptual and thought processes and propensities for certain behaviors.

Originally based on psychoanalysis , interpretation now relies more on empirically derived norms and an ideographic formulation approach assessing cognitive and perceptual constructs (Meyer & Kurtz, 2006).

With appropriate training and methods to promote reliable coding and valid interpretation, the Rorschach can serve as a broadband performance-based instrument complementing other assessments (McGrath & Carroll, 2012).

Critical Evaluation

- Depth of Insight : Can provide rich, qualitative data about an individual’s unconscious motives, conflicts, and interpersonal dynamics. Because it’s less likely to elicit socially desirable responses, the individual is unlikely to deduce what is being measured, ensuring that behavior remains natural and consistent.

- Flexibility : Suitable for diverse populations and can be adapted for different age groups.

- Less Direct : As an indirect method, it might allow individuals to express thoughts and feelings they might withhold with direct questioning.

Disadvantages

- Subjectivity : The major criticism of projective techniques is their lack of objectivity. Such methods are unscientific and do not objectively measure attitudes in the same way as a Likert scale. Interpretation highly depends on the examiner’s skill, leading to potential variability in conclusions.

- Lack of Standardization : There isn’t a standardized scoring system, which can limit the test’s reliability and validity.

- Time-Consuming : Both administration and interpretation can be lengthy.

- Cultural Bias : Some cards or interpretations might not be culturally appropriate or relevant for all individuals.

- Terminology : The term “projective” has multiple connotations in psychoanalytic theory, including the defense mechanism of externalizing one’s unacceptable feelings, as well as just idiosyncratic interpretation of ambiguous stimuli in general. This ambiguity creates questionable psychoanalytic assumptions when applied to tests.

Bellak, L., & Bellak, S. S. (1949). Children’s Apperception Test.

Bellak, L. (1954). The Thematic Apperception Test and the Children’s Apperception Test in clinical use.

Bellak, L., & Abrams, D. M. (1997). The Thematic apperception test, the children’s apperception test, and the senior apperception technique in clinical use . Allyn & Bacon.

Buck, J. N. (1948). The HTP technique; a qualitative and quantitative scoring manual. Journal of Clinical Psychology .

Eron, L. D. (1950). A normative study of the Thematic Apperception Test. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 64 (9), i–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093627

Exner, J. E., Jr. (2003). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system: Vol. I. Basic foundations and principles of interpretation (4th ed.). Wiley

Flanagan, R., & Motta, R. W. (2007). Figure drawings: A popular method. Psychology in the Schools , 44 (3), 257-270.

Goodenough, F. L. (1926). Measurement of intelligence by drawings . World Book Company.

Frank, L. K. (1939). Projective methods for the study of personality. The Journal of Psychology, 8 (2), 389–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1939.9917671

Harris, D. (1963). Children’s drawings as measures of intellectual maturity. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Imuta, K., Scarf, D., Pharo, H., & Hayne, H. (2013). Drawing a Close to the Use of Human Figure Drawings as a Projective Measure of Intelligence. PLoS ONE, 8(3).

Kamphaus, R. W., & Pleiss, K. L. (1991). Draw-a-Person techniques: Tests in search of a construct. Journal of School Psychology , 29 (4), 395-401.

McGrath, R. E. (2008). The Rorschach in the context of performance-based personality assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90 (5), 465–475. Rorschach inkblot

McGrath, R. E., & Carroll, E. J. (2012). The current status of “projective” “tests.” In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology: Vol. 1. Foundations, planning, measures, and psychometrics (pp. 329–348). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13619-018

Meyer, G. J., & Kurtz, J. E. (2006). Advancing personality assessment terminology: Time to retire “objective” and “projective” as personality test descriptors. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87 (3), 223–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8703_01

Meyer, G. J., & Mihura, J. L. (2020). Performance-based techniques. In M. Sellbom & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of clinical assessment and diagnosis (pp. 278–290). Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, G. J., Viglione, D. J., Mihura, J. L., Erard, R. E., & Erdberg, P. (2011). Rorschach Performance Assessment System: Administration, coding, interpretation, and technical manual . Rorschach Performance Assessment System.

Mihura, J. L., Meyer, G. J., Dumitrascu, N., & Bombel, G. (2013). The validity of individual Rorschach variables: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the comprehensive system. Psychological Bulletin, 139 (3), 548–605. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029406

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality . Oxford University Press.

Naglieri, J. A., McNeish, T. J., & Bardos, A. N. (1988). Draw a Person [DAP]: A Quantitative Scoring System . Psychological Corporation.

Osgood, C.E, Suci, G., & Tannenbaum, P. (1957). The Measurement of Meaning . University of Illinois Press, 1

Piotrowski, C. (2015). On the decline of projective techniques in professional psychology training. North American Journal of Psychology, 17(2).

Reynolds, C. R., & Hickman, J. A. (2004). Draw-a-person Intellectual Ability Test for Children, Adolescents, and Adults . Pro-ed.

Rorschach, H. (1921). Psychodiagnostik . Bircher.

Scott, L. H. (1981). Measuring intelligence with the Goodenough-Harris Drawing Test. Psychological bulletin , 89 (3), 483.

Smith, D., & Dumont, F. (1995). A cautionary study: Unwarranted interpretations of the Draw-A-Person Test. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 26 (3), 298.

Weiner, I. B. (1994). The Rorschach Inkblot Method (RIM) is not a test: Implications for theory and practice. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62 (3), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_9

Definition:

The Projective Hypothesis is a concept in psychology that suggests individuals project their own unconscious desires and emotions onto others.

According to the Projective Hypothesis, people tend to ascribe their own thoughts, feelings, and motives to others, often without realizing it. This projection is believed to occur due to the individual’s inability to fully acknowledge or accept these aspects of themselves consciously.

Background:

The Projective Hypothesis was first introduced by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who proposed that projection serves as a defense mechanism to avoid dealing with one’s inner conflicts or unacceptable impulses. Freud believed that people project their deepest fears, insecurities, and desires onto others, as a way of distancing themselves from these uncomfortable feelings.

Mechanisms:

Projection can occur in various ways, including:

- Attribution : Individuals attribute their own thoughts, beliefs, or intentions to others, assuming that everyone else thinks or feels the same way they do.

- Perception : People may perceive others as having certain qualities or flaws that are actually projections of their own personality traits or unresolved issues.

- Empathy : Projecting one’s emotions onto others can lead to increased empathy or understanding, as individuals feel a connection to others who they believe share their feelings.

Here are a few examples illustrating the Projective Hypothesis:

- A person who frequently experiences jealous thoughts may accuse their partner of infidelity, projecting their own mistrust and insecurities onto their relationship.

- Someone who is highly ambitious and driven may assume that everyone around them possesses the same level of ambition, unable to recognize that their motivation may be unique.

- An individual with repressed anger may interpret innocuous comments as hostile or offensive, reacting strongly due to projecting their own unresolved anger onto others.

Conclusion:

The Projective Hypothesis suggests that people involuntarily project their own unconscious desires, emotions, and impulses onto others. By recognizing and understanding projection, individuals can gain insight into their own inner workings and potentially improve their relationships and self-awareness.

The Projective Hypothesis of Personality Assessment

Discover how psychologists used general principles and conceptual similarities of projection to establish the sub-discipline of projective assessments.

In our last post we explored the noteworthy etymology of the word projection. Its development carries many nuances—some of which are still the subject of debate—that contribute to the many uses and applications of the concept. While the origins of projection have their roots in psychoanalysis, the foundation of projective techniques was more widespread than one school of thought, and instead was built on general principles by which to study personality. This is a critical and commonly overlooked distinction, as these projective techniques were not originally involved with the processes of psychoanalytic projection, specifically the Freudian concept of defense mechanisms (Lindzey, 1961, p. 38). In this post, we’ll show you the logic of how psychologists used general principles and conceptual similarities of projection to establish the subdiscipline of projective assessments .

The Origins of the Term “Projective Methods”

To understand the formal projective hypothesis, we must first understand the origin of projective methods.

The origins of projective techniques are intricately folded and somewhat convoluted. While there were many scholars who influenced the development of projective techniques, economist and educator Lawrence K. Frank proposed the term projective methods to describe the techniques used to “reveal the way an individual personality organizes experience, in order to disclose or at least gain insight into the individual’s private world of meanings, significances, patterns, and feelings” (Frank, 1939, p. 402).

Frank proposed that the study of personality should focus on the processes of organizing experiences (e.g., the experience when looking at inkblots) and psychological materials (e.g., meanings) in real-time, with respect to distinctive cultural patternings. This position is best captured by a psychocultural approach.

In his 1939 paper, Projective methods for the study of personality , Frank described the method where a personality—when provided with an interactive environment, or as he puts it, a “stimulus-situation”—can project this private world onto the environment. This occurs because the individual has to “organize the field, interpret the material and react affectively to it” (Frank, 1939, p. 403).

Frank noted that a “stimulus-situation” should—for the purposes of projecting inner mental states out into the environment—contain as little structural and social or cultural patterning as possible. Through the general mechanism of projection, a person may reveal aspects of their private world (i.e. personality). In particular, these projective techniques aim to reveal what the subject keeps private, or as Frank stated several times, “what he cannot or will not say” (Frank, 1939, p. 404, 408). While this private world indeed alludes to aspects of the non-conscious mind, it should not be confused with Freud’s conceptualization of repression and the individual’s unconscious act of keeping harmful content out of consciousness.

Frank’s writings touch on several topics that are foundational to the projective hypothesis. As such, Frank is commonly credited with coining the projective hypothesis, though the term itself was introduced later on.

What is the “Projective Hypothesis”?

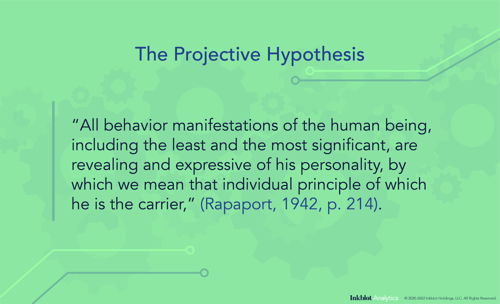

In 1942 David Rapaport, a significant figure in psychoanalytic psychology, coined the term “ Projective Hypothesis ,” and defined this hypothesis as “all behavior manifestations of the human being, including the least and the most significant, are revealing and expressive of his personality, by which we mean that individual principle of which he is the carrier” (Rapaport, 1942, p. 214).

While the projective hypothesis set a foundation for projective science to grow upon, it did not provide a direct connection for how researchers in projective science should develop their own methods and tests.

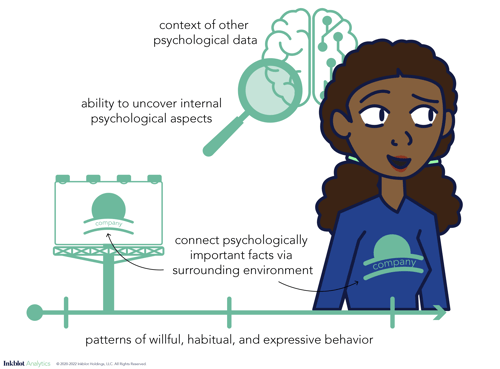

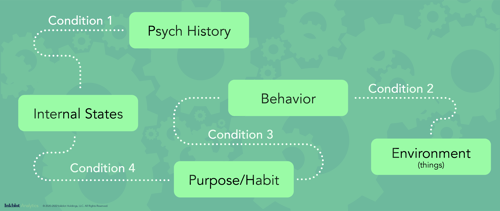

Therefore, Rapaport outlined 4 conditions, built on the Projective Hypothesis, that are required for a psychological assessment to be a projective test:

The ability to understand projections in the context of other psychological data.

The ability to connect psychologically important facts via the surrounding environment.

The ability to focus on patterns of willful, habitual, and expressive behavior.

The ability to uncover internal psychological aspects of the individual.

What are the four necessary conditions every projective method/test needs to have according to the projective hypothesis?

Condition 1 : The ability to understand projections in the context of other psychological data. This first condition of a projective technique is its ability to constitute individual facts about a person’s experience examined from interviews as well as personal records. These patterns of behavior, and in singular cases behavioral events, are useful for providing a foundation when analyzing an individual’s current state via projection. For example, if a person has a family history of psychiatric disorders that are unknown to an examiner, it could lead to alternative, uninformed explanations for their projections. A projective technique must allow for the ability to substantiate interpretations of projections in light of other psychological evidence, like life history data.

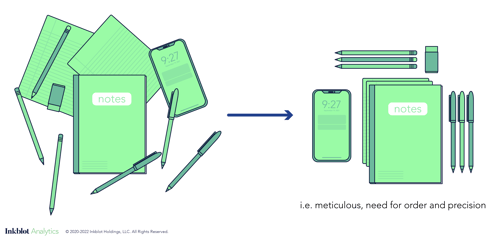

Condition 2: The ability to connect psychologically important facts via the surrounding environment. The second necessary condition for a projective technique is directly linked to what would later become a pillar of consumer psychology--the link between mind and materials. Rapaport provides the example of the clothes a person wears and the materials they decorate the interior of their home with. These products are seen as both functional (e.g. to stay warm in the winter, or protected from the sun during summer) and symbolic (e.g. as reflections of personal identity). But we only know that certain items are symbolic, or meaningful, if participants can indicate it as such within the test. Consequently, how the person organizes the surrounding environment helps connect the test data with psychologically important facts.

Condition 3: The ability to focus on patterns of willful, habitual, and expressive behavior. This third condition describes how important it is to note goal-oriented modifications to a specific environment, at a given time. These goal-oriented patterns reveal purpose-driven actions (or executions of will), which are critical for understanding the underlying aspects of personality (Allport, 1937).

Condition 4: The ability to uncover internal psychological aspects of the individual. The fourth condition requires that a projective technique should be able to get at the perceptions, thoughts, and fantasies behind behavior, which have direct ties to individual needs and concerns. At times there may be an inherent dissociation between the internal and external worlds. We may intend to behave in a certain way, but our actions could say otherwise. On the other hand—as in the case of projection—we may unknowingly cast out a shadow of the internal onto the external world.

What kind of activities meet the necessary conditions of the projective hypothesis?

Rapaport’s four necessary conditions, built on the projective hypothesis, help provide guidelines for projective methods. But the remaining question to most projective methodologists is what is the best activity to employ in their test? What rigorous process would allow us to truly focus on the internal psychological aspect of a person, reflected in the person’s environment by their expressive, purpose-driven behaviors, and validated with connections to other psychological data?

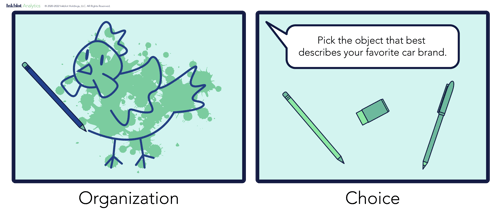

Rapaport suggests two activities that can be used in projective methods--choice and organization. Rapaport argued that the choices a person makes, and the manner in which they organize these choices, can be expressive of the personality. Rapaport contended that choice and organization are not entirely mutually exclusive, but rather two sides of the same coin. One becomes dominant over the other depending on the method used. However, only by understanding the pros and cons of each methodological approach can we gain a greater knowledge of the outcome of projection (Rapaport, 1942).

Consider a test where you choose which objects from a set belong with the sample object. One of the benefits of this approach is the open-ended observation of their concept formation (i.e., seeing in real time how they compare and contrast test objects with the sample object). However, a downside of choice methodologies is the potential limitations in a person’s ability to project by conventional response patterning. The key for choice-based methods is developing it in a way that circumvents cultural “default” patterns of responding.

On the other hand, if the test stimulus is more ambiguous, organization tends to dominate as the activity of choice. For example, a Rorschach inkblot test tells you about a subject’s perceptions of form, color, and shading as they ascribe meaning through organizing the features of the test material. There are a potentially unlimited number of ways to respond to the test’s stimulus according to individual interpretation.

Regardless of whether or not the activity employed is choice or organization, one thing is clear--whatever the stimulus is that they’re choosing or organizing, it has to be ambiguous to allow for their personal meaning to be projected onto it. As Frank said: “More specifically, a projection method for study of personality involves the presentation of a stimulus-situation designed or chosen because it will mean to the subject, not what the experimenter has arbitrarily decided it should mean (as in most psychological experiments using standardized stimuli in order to be “objective”), but rather whatever it must mean to the personality who gives it, or imposes open it, his private, idiosyncratic meaning and organization. The subject then will respond to his meaning of the presented stimulus-situation by some form of action and feeling that is expressive of his personality” (Frank, 1939, p. 403 ).

What advantages are there to projective techniques given the projective hypothesis?

Rapaport proposed four additional sufficient criteria from a comparison of clinical observations. It is important to note that Rapaport outlined these four criteria as distinct advantages of projective techniques over subjective clinical observation.

Easy objective observation means that the test has no interpretive selection.

Easy objective registration allows for an uninhibited response to the stimulus.

Systematic scoring to compare within and between individuals posits that the projectively obtained material should be scored according to a schema.

Disguised tests mask the intentions of the projective techniques, such that the purpose of the test is unknown to the subject.

In Rapaport’s experience, clinical observation often yields subjective data in the sense that an interpretation is made from an infinite number of features of a given behavior. In other words, it is particularly susceptible to individual bias. Charles A. Dailey (1951,1960) elaborated on the faulty premises of assessment, suggesting that clinicians could predict with higher accuracy by accounting for the design of the test and how it is received by the subject. He also proposed three forms of bias that pervaded the practice of the time.

Pathological bias is a “tendency to see symptoms and defense mechanisms in everyone“ (Dailey, 1960, p. 20). Think back to our metaphor, “when you think like a hammer , everything looks like a nail .”

Abstract bias is the belief that personality is an abstract idea that is not closely related to behavior. In this view personality is static and intangible to the observer. Dailey proffered a quote from Abraham Maslow (1956) to describe the hazards of such a bias, “All intellectuals tend to become absorbed with abstractions, words and concepts, and forget … the fresh and concrete, the original real experience which is the beginning of all science” (Maslow, 1956, pp. 186).

Testing bias is the over reliance on standardized measurements and observations. Dailey concludes by calling for a change in cultural practice, in favor of a focus on increased importance on life-history methods and concepts.

Projective techniques offer an alternative form of psychological assessment. This usually makes it the subject of many critics. But Projective tests start with a fundamental axiom (i.e., the projective hypothesis), and have both necessary and sufficient guidelines for what is required to create them. Hopefully, by reading this post, you can see that there is a “method to the madness” when it comes to creating new projective tests, methods, and techniques.

[1] For a detailed account on the development of clinical practices, as well as the origination of the terms projective {tests, techniques, and methods} of projective techniques, please see pp. 31-38 in Gardner Lindzey’s 1961 book titled Projective techniques and cross-cultural research .

References:

Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: a psychological interpretation. Holt.

Dailey, C. A. (1951). The clinician and his predictions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 7, 270–273.

Dailey, C. A. (1960). The life history as a criterion of assessment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 7(1), 20-23.

Frank, L. K. (1939). Projective methods for the study of personality. Journal of Psychology. 402-403.

James, W. (2007), [1890]. The Principles of Psychology Vol. 1. Cosimo, Inc. 292.

Lindzey, G. (1961). Projective techniques and cross-cultural research. Appleton-Century-Crofts. 31-38.

Maslow, A. H. (1956). Toward a humanistic psychology. ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 186.

Rapaport, D. (1942). Principles underlying projective techniques. Character & Personality; A Quarterly for Psychodiagnostic & Allied Studies, 10, 213–219.

Rapaport, D., Gill, M., & Schafer, R. (1946). Diagnostic psychological testing: The theory, statistical evaluation, and diagnostic application of a battery of tests: Vol. 2. The Year Book Publishers.

Similar posts

A taxonomy of projective tests.

The inception of projective testing provided a springboard for all kinds of innovation and the creation of new testing methods.

Motivation Research: Case Studies

In 1959 Dichter conducted a successive series of projective tests to study FAB detergent.

Motivation Research: Using Projective Tests

Ernest Dichter extensively utilized projective tests in his practice and helped establish them as an acceptable method in market research.

Get notified on new psychological insights

Be the first to know about new psychological insights that can help you optimize customer touchpoints and drive business growth.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How a Projective Test Is Used to Measure Personality

A person's responses are thought to reflect unconscious feelings

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

A projective test is a type of personality test in which you offer responses to ambiguous scenes, words, or images. A person's responses to a projective test are thought to reflect hidden conflicts or emotions , with the hope that these issues can then be addressed through psychotherapy or other appropriate treatments.

History of the Projective Test

This type of test emerged from the psychoanalytic school of thought, which suggested that people have unconscious thoughts or urges. Projective tests are intended to uncover feelings, desires, and conflicts that are hidden from conscious awareness.

By interpreting responses to ambiguous cues, psychoanalysts hope to uncover unconscious feelings that might be causing problems in a person's life.

Training in projective testing in psychology graduate settings has rapidly declined over the past decade or so. Despite the controversy over their use, projective tests remain quite popular and are extensively used in both clinical and forensic settings.

At least one projective test was noted as one of the top five tests used in practice for 50% of 28 worldwide survey-based studies.

How a Projective Test Works

In many projective tests, people are shown an ambiguous image and then asked to give the first response that comes to mind. The key to projective tests is the ambiguity of the stimuli.

According to the theory behind such tests, using clearly defined questions can result in answers that are carefully crafted by the conscious mind . When you are asked a straightforward question about a particular topic, you have to spend time consciously creating an answer.

This can introduce biases and even untruths, whether or not you're trying to deceive the test provider. For example, a respondent might give answers that are perceived as more socially acceptable or desirable but are perhaps not the most accurate reflection of their true feelings or behavior.

By providing you with a question or stimulus that is not clear, your underlying and unconscious motivations or attitudes are revealed.

The hope is that because of the ambiguous nature of the questions, people might be less able to rely on possible hints about what they think the tester expects to see. As a result, they are hopefully less tempted to "fake good," or make themselves look good, as a result.

Types of Projective Tests

There are a number of different types of projective tests. Some of the best-known examples include:

The Rorschach Inkblot Test

This test was one of the first projective tests developed and continues to be one of the best-known and most widely used. Developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921, the test consists of 10 different cards that depict an ambiguous inkblot.

People are shown one card at a time and asked to describe what they see in the image. The responses are recorded verbatim by the tester. Gestures, tone of voice, and other reactions are also noted.

The results of the test can vary depending on which of the many existing scoring systems the examiner uses.

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)

In the TAT test , people are asked to look at a series of ambiguous scenes and then to tell a story describing the scene. This includes describing what is happening, how the characters are feeling, and how the story will end.

The examiner then scores the test based on the needs, motivations, and anxieties of the main character, as well as how the story eventually turns out.

The Draw-A-Person Test

This type of projective test involves exactly what you might imagine. People draw a person and the image that they created is then assessed by the examiner.

To score the test, the test interpreter might look at a number of factors. These may include the size of particular parts of the body or features, the level of detail given to the figure, as well as the overall shape of the drawing.

Like other projective tests, the Draw-A-Person test has been criticized for its lack of validity.

A test interpreter might suggest that certain aspects of the drawing are indicative of particular psychological tendencies. However, it might simply mean that the individual has poor drawing skills.

The test has been used as a measure of intelligence in children, but research comparing scores on the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence to the Draw-A-Person test found a very low correlation between the two scores.

The House-Tree-Person Test

In this type of projective test, people are asked to draw a house, a tree, and a person. Once the drawing is complete, they are asked a series of questions about the images they have drawn.

The test was originally designed by John Buck and included a series of 60 questions to ask the respondent, although test administrators may also come up with their own questions or follow-up queries to further explore the subject's responses. For example, the test administrator might ask of the house drawing:

- Who lives here?

- Who visits the person who lives here?

- Is the person who lives here happy?

Weaknesses of a Projective Test

Projective tests are most frequently used in therapeutic settings. In many cases, therapists use these tests to learn qualitative information about individuals.

Some therapists may use projective tests as a sort of icebreaker to encourage people to discuss issues or examine their thoughts and emotions.

While projective tests have some benefits, they also have a number of weaknesses and limitations, including:

- Projective tests that do not have standard grading scales tend to lack both validity and reliability . Validity refers to whether or not a test is measuring what it purports to measure, while reliability refers to the consistency of the test results.

- Scoring projective tests is highly subjective, so interpretations of answers can vary dramatically from one examiner to the next.

- The respondent's answers can be heavily influenced by the examiner's attitudes or the test setting.

Nunez, K. Projective techniques in qualitative market research . American Marketing Association.

Piotrowski, C. On the decline of projective techniques in professional psychology training . North American Journal of Psychology . 2015;17:259-266.

Sarason, I. G. Personality assessment . Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

Imuta K, Scarf D, Pharo H, Hayne H. Drawing a close to the use of human figure drawings as a projective measure of intelligence . PLoS ONE . 2013;8(3):e58991. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058991

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Projective Technique

- Reference work entry

- pp 2046–2047

- Cite this reference work entry

- Stephanie A. Kolakowsky-Hayner 5

577 Accesses

Ambiguous personality assessment ; Free-response measures ; Unrestricted-response technique

Projective techniques are a subset of personality testing in which the examinee is given a simple unstructured task, with a goal of uncovering personality characteristics. Projective techniques are often the most recognizable yet the most psychometrically controversial psychological testing technique. Based on the projective hypothesis, projective stimuli are purposefully ambiguous with the goal of eliciting the examinee’s true feelings, desires, fears, motives, and other unconscious personality characteristics. While neuropsychologists typically use objective measures of analysis, most only utilize projective techniques if there is suspected psychiatric diagnosis, rather than simply a suspected or known neurological diagnosis (Sweet, Moberg, & Suchy, 2000 ). The most common projective techniques include the Rorschach Inkblot Test (also known as the Rorschach or simply The...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

References and Readings

Klopfer, W. G., & Taulbee, E. S. (1976). Projective tests. Annual Review of Psychology, 27 , 543–568.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lilienfeld, S. O., Wood, J. M., & Garb, H. N. (2000). The scientific status of projective techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 1 , 27–66.

Google Scholar

Sweet, J. J., Moberg, P. J., & Suchy, Y. (2000). Ten-year follow-up survey of clinical neuropsychologists: Part I. Practices and beliefs. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 14 , 18–37.

Watkins, C. E., Campbell, V. L., & McGregor, P. (1988). Counseling psychologists’ uses of and opinions about psychological tests: A contemporary perspective. The Counseling Psychologist, 16 , 476–486.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Director, Rehabilitation Research, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center Rehabilitation Research Center, 751 South Bascom Ave., 95128, San Jose, CA, USA

Stephanie A. Kolakowsky-Hayner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Professor of Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry Virginia Commonwealth University – Medical Center Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, VCU, 980542, Richmond, Virginia, 23298-0542, USA

Jeffrey S. Kreutzer

Kessler Foundation Research Center, 1199 Pleasant Valley Way, West Orange, NJ, 07052, USA

John DeLuca

Professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Neurology and Neuroscience, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey – New Jersey Medical School, New Jersey, USA

Independent Practice, 564 M.O.B. East, 100 E. Lancaster Ave., Wynnewood, PA, 19096, USA

Bruce Caplan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kolakowsky-Hayner, S.A. (2011). Projective Technique. In: Kreutzer, J.S., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B. (eds) Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79948-3_2096

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79948-3_2096

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-79947-6

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-79948-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Projective hypothesis and projective tests have been subjected to severe criticisms as well as enthusiastic glorification at different points of time. Since its origin is located within psychoanalysis, its acceptance as a basis for personality assessment also depended, at least partially, on the attitude toward the discipline of psychoanalysis ...

Projective tests in psychology are assessment tools that present individuals with ambiguous stimuli, prompting them to interpret or create stories about them. The responses reveal underlying emotions, desires, and conflicts, based on the idea that people project their unconscious feelings onto the ambiguous stimuli. Common examples include the Rorschach inkblot test and the Thematic ...

The Projective Hypothesis is a concept in psychology that suggests individuals project their own unconscious desires and emotions onto others. Overview: According to the Projective Hypothesis, people tend to ascribe their own thoughts, feelings, and motives to others, often without realizing it.

What are the four necessary conditions every projective method/test needs to have according to the projective hypothesis? Condition 1: The ability to understand projections in the context of other psychological data. This first condition of a projective technique is its ability to constitute individual facts about a person's experience examined from interviews as well as personal records.

The projective hypothesis is a fundamental concept in psychology, particularly in the context of projective testing. It posits that when individuals are presented with ambiguous or vague stimuli, their responses will be shaped by their unconscious desires, feelings, experiences, and internal conflicts.

A projective test uses ambiguous stimuli to assess personality. Learn how a person's responses to a projective test are thought to reflect hidden emotions. ... Training in projective testing in psychology graduate settings has rapidly declined over the past decade or so. Despite the controversy over their use, projective tests remain quite ...

Projective methods can be used to good effect with children and adolescents as well as adults. The basic interpretive conclusions and hypothesis that attach to projective test variables apply regardless of the age of the subject, provided that examiners determine the implications of their data in the light of normative developmental expectations.

In psychology, a projective test is a personality test designed to let a person respond to ambiguous stimuli, presumably revealing hidden emotions and internal conflicts projected by the person into the test. This is sometimes contrasted with a so-called "objective test" / "self-report test", which adopt a "structured" approach as responses are analyzed according to a presumed universal ...

Projective Hypothesis. The Projective Hypothesis posits that the use of unstructured and ambiguous stimuli such as projective tests like the Rorschach inkblot test or the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) are important and necessary as a means of bypassing a client's defenses and to discover their unconscious needs, motives, and conflicts. These types of tests rely on the test subject's ...

Projective techniques are often the most recognizable yet the most psychometrically controversial psychological testing technique. Based on the projective hypothesis, projective stimuli are purposefully ambiguous with the goal of eliciting the examinee's true feelings, desires, fears, motives, and other unconscious personality characteristics.