Getting First Graders Started With Research

Teaching academically honest research skills helps first graders learn how to collect, organize, and interpret information.

Your content has been saved!

Earlier in my career, I was told two facts that I thought to be false: First graders can’t do research, because they aren’t old enough; and if facts are needed for a nonfiction text, the students can just make them up. Teachers I knew went along with this misinformation, as it seemed to make teaching and learning easier. I always felt differently, and now—having returned to teaching first grade 14 years after beginning my career with that age group—I wanted to prove that first graders can and should learn how to research.

A lot has changed over the years. Not only has the science of reading given teachers a much better understanding of how to teach reading skills , but we now exist in a culture abundant in information and misinformation. It’s imperative that we teach academically honest research skills to students as early as possible.

Use a Familiar Resource, and Pair it with a Planned Unit

How soon do you start research in first grade? Certainly not at the start of the year with the summer lapse in skills and knowledge and when new students aren’t yet able to read. By December of this school year, skills had either been recovered or established sufficiently that I thought we could launch into research. This also purposely coincided with a unit of writing on nonfiction—the perfect pairing.

The research needed an age-related focus to make it manageable, so I chose animals. I thought about taking an even safer route and have one whole class topic that we researched together, so that students could compare notes and skills. I referred back to my days working in inquiry-based curriculums (like the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program) and had students choose which animal to study. Our school librarian recommended that we use Epic because the service has an abundance of excellent nonfiction animal texts of different levels.

Teach the Basics for Organized Research

I began with a conversation about academic honesty and why we don’t just copy information from books. We can’t say this is our knowledge if we do this; it belongs to the author. Instead, we read and learn. Then, we state what we learned in our own words. Once this concept is understood, I model how to do this by creating a basic step-by-step flowchart taught to me by my wife—a longtime first-grade and kindergarten teacher and firm believer in research skills.

- Read one sentence at a time.

- Turn the book over or the iPad around.

- Think about what you have learned. Can you remember the fact? Is the fact useful? Is it even a fact?

- If the answer is no, reread the sentence or move onto the next one.

- If the answer is yes, write the fact in your own words. Don’t worry about spelling. There are new, complex vocabulary words, so use your sounding-out/stretching-out strategies just like you would any other word. Write a whole sentence on a sticky note.

- Place the sticky note in your graphic organizer. Think about which section it goes in. If you aren’t sure, place it in the “other facts” section.

The key to collecting notes is the challenging skill of categorizing them. I created a graphic organizer that reflected the length and sections of the exemplar nonfiction text from our assessment materials for the writing unit. This meant it had five pages: an introduction, “what” the animal looks like, “where” the animal lives, “how” the animal behaved, and a last page for “other facts” that could become a general conclusion.

Our district’s literacy expert advised me not to hand out my premade graphic organizer too soon in this process because writing notes and categorizing are two different skills. This was my intention, but I forgot the good advice and handed out the organizer right away. This meant dedicating time for examining and organizing notes in each combined writing and reading lesson. A lot of one-on-one feedback was needed for some students, while others flourished and could do this work independently. The result was that the research had a built-in extension for those students who were already confident readers.

Focus on What Students Need to Practice

Research is an essential academic skill but one that needs to be tackled gradually. I insisted that my students use whole sentences rather than words or phrases because they’re at the stage of understanding what a complete sentence is and need regular practice. In this work, there’s no mention of citation language and vetting sources; in the past, I’ve introduced those concepts to students in fourth grade and used them regularly with my fifth-grade students. Finding texts that span the reading skill range of a first-grade class is a big enough task.

For some of the key shared scientific vocabulary around science concepts, such as animal groups (mammals, etc.) or eating habits (carnivore, etc.), I created class word lists, having first sounded out the words with the class and then asked students to attempt spelling them in their writing.

The Power of Research Can Facilitate Student Growth

I was delighted with the results of the research project. In one and a half weeks, every student had a graphic organizer with relevant notes, and many students had numerous notes. With my fourth- and fifth-grade students, I noticed that one of the biggest difficulties for them was taking notes and writing them in a way that showed a logical sequence. Therefore, we concluded our research by numbering the notes in each section to create a sequential order.

This activity took three lessons and also worked for my first graders. These organized notes created an internal structure that made the next step in the writing process, creating a first draft of their nonfiction teaching books, so much easier.

The overall result was that first graders were able to truly grasp the power of research and gathering accurate facts. I proved that young children can do this, especially when they work with topics that already fascinate them. Their love of learning motivated them to read higher-level and more sophisticated texts than they or I would normally pick, further proving how interest motivates readers to embrace complexity.

Teaching Research Skills to Elementary Students

Teaching research skills to elementary students takes the entire year. Start with short, teacher-generated activities. Continue with guided subject-area projects. Finally, your students will be ready for independent research.

Table of contents

Introducing genres of writing, teaching point of view, front-loading writing skills, locating and analyzing information, choosing a topic, evaluating, selecting, and citing sources of information, gathering information, organizing information, drafting and revising, enjoy teaching research skills to elementary students.

Our favorite fourth grade teacher sat at the side table with her student teacher. “Let’s continue planning our ELA block ,” she said. “Today, we’ll talk about teaching research skills to upper elementary students.”

“Great!” Mr. Grow responded. “When does the project start?”

Ms. Sneed smiled slightly. “Not one project,” she said. “Dozens. Let me explain.”

What to Do Before Teaching Research Skills

“Before we begin teaching research,” Ms. Sneed said, “we’ll build some background skills. For example, kids need to know the difference between fiction and nonfiction, as well as first- and third-person.”

Without warning, Ms. Sneed spread her arms out wide. “First,” she said, “we’ll talk about the two sides of writing .

“On this side,” she said, wiggling the fingers on her right hand, “we have expressive writing. This is where we find fiction. On this side, writers use a story arc for narrative writing. Elements include characters, settings, plots, and themes. Writing on this side tends to use sensory language and dialogue.”

Now Ms. Sneed wiggled the fingers on her left hand. “Over here, we find informative writing. Obviously, research belongs here. On this side, writers use what I refer to as the hamburger format. The top bun introduces the topic and tells the main idea. The burgers offer the meat of the piece with sup

porting information. Finally, the bottom bun concludes.”

Pointing to the portion of her left arm nearest to her body, she continued. “Argumentative writing falls on this side. It’s written with the hamburger format and offers lots of facts. The purpose, however, is to persuade. Therefore, the author carefully organizes information to support their own opinion. Before they can choose reliable sources, kids should be able to spot writing slanted to a certain point of view.”

Mr. Grow nodded. “I never thought about writing that way before. When will we teach this?”

“Early and often,” Ms. Sneed responded. Every time kids read or write, I spread my arms out wide. Then we discuss where the piece will fall on this spectrum . This simple practice improves kids’ writing, as well as their reading comprehension.”

Next, the mentor opened her laptop. With just a few clicks, she opened a unit on point of view . “In fourth grade,” she explained, “I focus on first- and third-person points of view. Of course, understanding pronouns like I and me, they and them, helps. This lays the groundwork for discriminating between informative and argumentative writing.”

Mr. Grow shook his head slightly. “Honestly, I never knew that all of these concepts were interconnected. Let me see if I’ve got this straight. Before teaching research writing, kids need to understand point of view. But in order to do that, they need to know first- and third-person pronouns.”

“Yep,” his mentor replied with a grin. “Nothing’s really taught in isolation. Good teachers purposefully sequence learning experiences. That way, students have the background information needed for each activity.”

“As we move through the first quarter,” Ms. Sneed continued, “we’ll also work on writing skills. Regardless of the genre, kids will use transition terms to link ideas, select precise language, and vary sentences.”

Ms. Sneed turned her attention to her laptop. Then she turned the screen toward Mr. Grow.

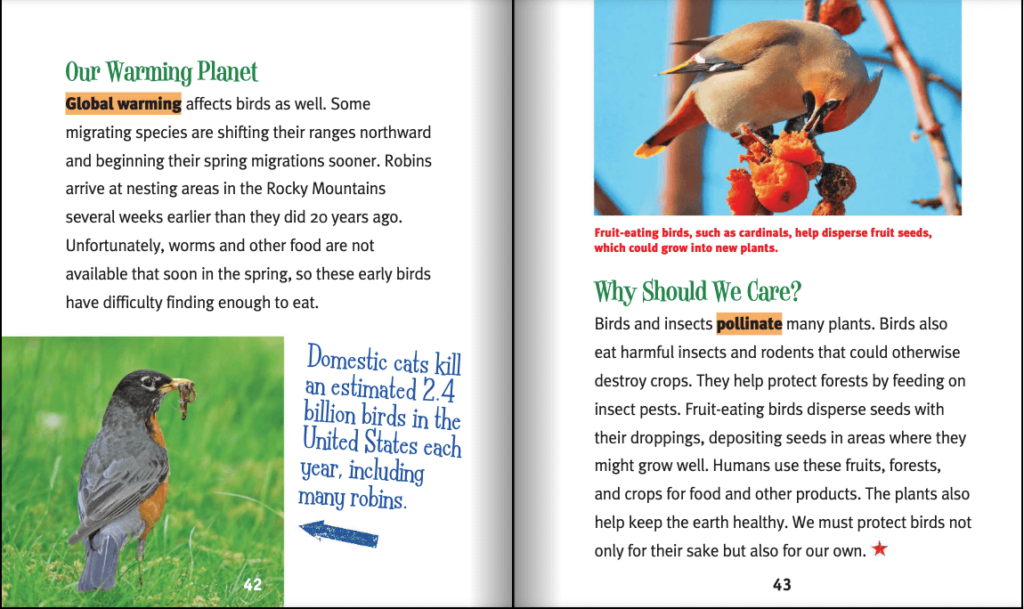

“For this activity ,” she said, “kids don’t actually research. Instead, they check facts about several animals. We provide questions and sites. As the students look for information, they also analyze each site’s features. Finally, they rank the sites and list three top features. For example, they might say that a good website includes images, sidebars, and graphs.”

Teaching Research Skills with Guided Subject-Area Research

“After teaching these research skills, I like to engage kids in a variety of seasonal or subject-area reports. For example, as we study women’s suffrage, each student can research a key figure .”

Once again, Ms. Sneed clicked around on her laptop. “Check this out. For a super short research project, kids can fill out this first page. It only asks for basic information about the person. If, however, you want kids to look deeper into the person’s life, they can analyze difficulties in their life and who helped them. To promote greater historical awareness, students can also consider how history changed the person and the person changed history.

“When they finish, kids write multi-paragraph essays on themed paper and hang it with a picture of the person. It makes a great display in the hall or classroom.”

“Nice,” said Mr. Grow. “Then they can read one another’s papers to learn more.”

“Exactly. It also helps if the principal comes in for an observation. That way, he sees learning in action – right on the classroom wall.”

Teaching Research Skills with Independent Projects

Ms. Sneed shifted in her seat and smiled. “Once kids have a few guided projects under their belts, they’re finally ready to try it on their own. Of course, we’ll continue teaching research skills along the way.”

Once again, she turned to her laptop. “I’d like to show you a project that’s ready to go. As you’ll see, the teacher will still provide guidance. But kids become much more independent.”

She pointed at the screen and explained page by page.

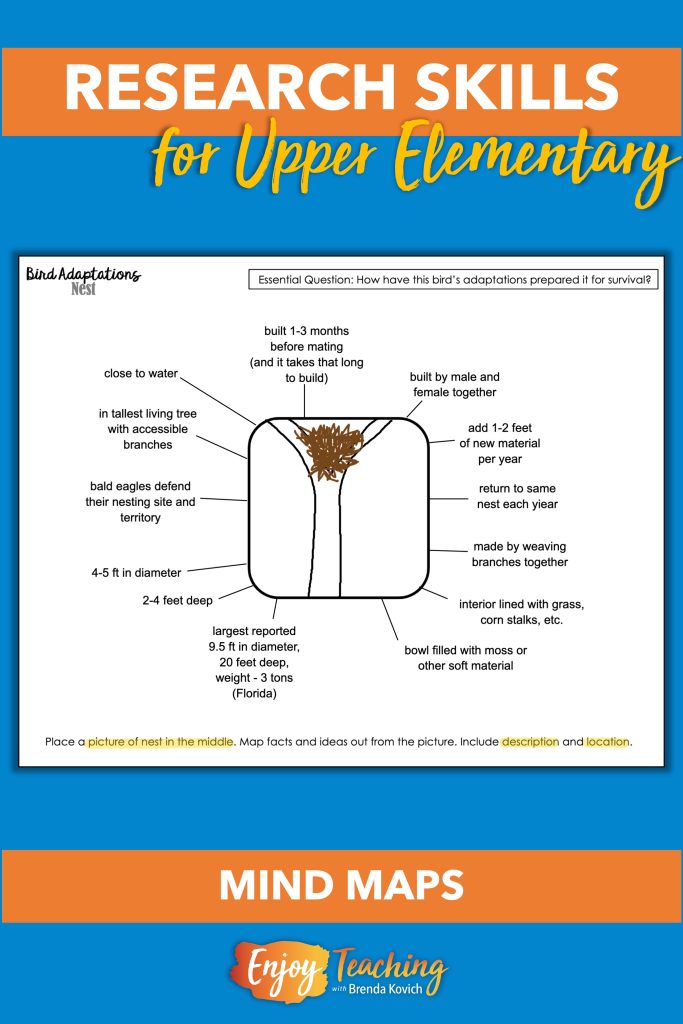

“This activity focuses on birds and their adaptations . In groups of three, kids select a tropical, temperate, and arctic bird from a specific group. Here, we’re teaching research skills related to limiting a topic. Students need to know that topics shouldn’t be too broad or too narrow.”

“In other words,” Mr. Grow said, “they should be just right. Sort of like the Goldilocks principle.”

Ms. Sneed nodded. “Additionally, kids need to be able to find plenty of information on the topic. After they choose their birds, I ask them to do a quick search. If they can’t find enough, they must choose another topic. Furthermore, if everything out there is written for adults, they should choose something else.

“This step is critical. Otherwise, a student may waste several days on a dead-end topic.”

“Before moving on, we spend time teaching an important research skill: evaluating sources. They must be relevant, reliable, factual, accurate, and objective.

“You can do this in several ways. At first, you may want to talk through the list while kids look at a site. Then they can use a checklist . Eventually, we want this to be second nature.”

Ms. Sneed slid a list across the table for Mr. Grow to see.

- Relevant – Does this source contain information that will support my research topic? Was the source created for someone like me (e.g., for a fourth grader)?

- Reliable – Was it created by a trustworthy person or organization?

- Factual and Accurate – Is the information factual? Can I confirm this information with other sources (or does the source cite it sources)? Is the information up-to-date?

- Objective – Has the creator presented information to support multiple points of view?

Returning to her laptop, Ms. Sneed scrolled through some note-taking sheets. “When teaching research skills to elementary students, we must provide guidance for gathering and organizing information.”

She pointed to a sample page. In the middle, Mr. Grow noticed a picture of a nest. Branching out in a web, he saw notes about eagles’ homes.

“This,” said Ms. Sneed, “is a mind map. It promotes divergent thinking. As you can see, this student has found and listed lots of facts.

“At this grade level, I provide mind maps for specific categories of information. In this case, for example, kids get pages for appearance, habits, and habitat. Of course, they can add other information on a blank sheet.”

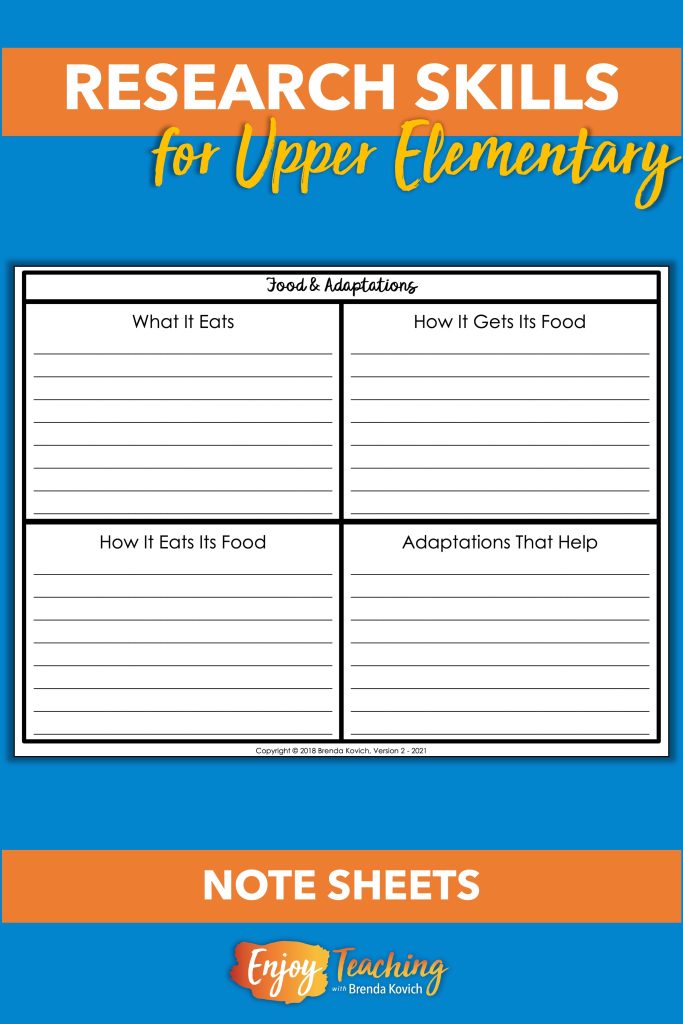

Note Sheets

Next, she scrolled to a page with four sections. “When I first began teaching, I tried traditional note cards with my students. What a disaster. At this age, kids lose the cards and have trouble sorting them. Then I came up with the idea of note sheets.

“Each page has four cards, all with similar topics. For example, on this sheet, kids take notes on food and adaptations. They sort the information by what they eat, how they get it, how they eat it, and adaptations that accommodate all of this.”

“That’s brilliant!” Mr. Grow exclaimed.

“Thanks. Best of all, it works. With this method, we train students to categorize. It really helps to organize their writing.

“In fourth grade, my students are only allowed to take notes in short phrases. They’re not allowed to quote until fifth grade. This way, kids master paraphrasing, and plagiarism isn’t an issue.”

Quickly, she scrolled to the next page. “As you see here, I like to use boxes and bullets. Kids write the main idea, or topic sentence in the box and supporting details next to the bullets.”

“After filling in the boxes and bullets, the paper practically writes itself. Drafting is easy.

“When that’s finished, kids revise using familiar strategies: improving word choice, adding transitions, varying sentences, etc.

“I like to use checklists for peer or individual editing. That encourages them to be self-sufficient, and my life is easier.”

“So there you have it! Everything you ever wanted to know about teaching research skills to elementary students. In fourth grade, we start with prerequisite concepts. Then we conduct a bunch of short research related to seasonal or subject-area topics. Finally, kids work on independent research projects. I love watching them become autonomous learners!”

- ELEMENTARY TEACHING , LITERACY

How to Teach Research Skills to Elementary Students in 2024

Research skills are incredibly important in the world we live in today. When we come across a problem or a question, what do we do? We quickly search online to find the answer. We are using our research skills while we are doing this. Read below to learn how to teach research skills to elementary students! This will help you prepare your twenty-first century learners for the ever-changing world we live in. You’ll have the confidence to create opportunities to apply these skills to research projects like this animal research project .

What are Research Skills?

Research skills is the ability to search for information about a topic, evaluate that information efficiently, and share findings in an organized way.

What Research Skills do Elementary Students Need?

Your elementary students are required to learn research skills if your state uses the Common Core or TEKS. Read below to learn what specific research standards your grade level covers.

Research Standards in Common Core

The standards listed below are a good starting point for figuring out how to teach research skills to your elementary students.

Kindergarten

- ELA.W.K.7 : Participate in shared research and writing projects.

- ELA.W.K.8 : With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question.

First Grade

- ELA.W.1.7 : Participate in shared research and writing projects.

- ELA.W.1.8 : With guidance and support from adults, recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question.

Second Grade

- ELA.W.2.7 : Participate in shared research and writing projects.

- ELA.W.2.8 : Recall information from experiences or gather information from provided sources to answer a question.

Third Grade

- ELA.W.3.7 : Conduct short research projects that build knowledge about a topic.

- ELA.W.3.8 : Recall information from experiences or gather information from print and digital sources; take brief notes on sources and sort evidence into provided categories.

Fourth Grade

- ELA.W.4.7 : Conduct short research projects that build knowledge through investigation of different aspects of a topic.

- ELA.W.4.8 : Recall relevant information from experiences or gather relevant information from print and digital sources; take notes and categorize information, and provide a list of sources.

- ELA.4.9 : Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- ELA.4.9.B : Apply grade 4 Reading standards to informational texts.

Fifth Grade

- ELA.W.5.7 : Conduct short research projects that use several sources to build knowledge through investigation of different aspects of a topic.

- ELA.W.5.8 : Recall relevant information from experiences or gather relevant information from print and digital sources; summarize or paraphrase information in notes and finished work, and provide a list of sources.

- ELA.W.5.9 : Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- ELA.W.5.9.B : Apply grade 5 Reading standards to informational texts.

Research Standards in TEKS

The standards listed below are a good starting point for figuring out how to teach research skills to your students.

- Generate questions for formal and informal inquiry with adult assistance. (TEKS 12A)

- Develop and follow a research plan with adult assistance. (TEKS 12B)

- Gather information from a variety of sources with adult assistance. (TEKS 12C)

- Demonstrate understanding of information gathered with adult assistance. (TEKS 12D)

- Use an appropriate mode of delivery, whether written, oral, or multimodal, to present results. (TEKS 12E)

- Generate questions for formal and informal inquiry with adult assistance. (TEKS 13A)

- Develop and follow a research plan with adult assistance. (TEKS 13B)

- Identify and gather relevant sources and information to answer the questions with adult assistance. (TEKS 13C)

- Demonstrate understanding of information gathered with adult assistance. (TEKS 13D)

- Use an appropriate mode of delivery, whether written, oral, or multimodal, to present results. (TEKS 13E)

- Identify and gather relevant sources and information to answer the questions. (TEKS 13C)

- Identify primary and secondary sources. (TEKS 13D)

- Demonstrate understanding of information gathered. (TEKS 13E)

- Cite sources appropriately. (TEKS 13F)

- Use an appropriate mode of delivery, whether written, oral, or multimodal, to present results. (TEKS 13G)

- Generate questions on a topic for formal and informal inquiry. (TEKS 13A)

- Identify and gather relevant information from a variety of sources. (TEKS 13C)

- Recognize the difference between paraphrasing and plagiarism when using source materials. (TEKS 13F)

- Create a works cited page. (TEKS 13G)

- Use an appropriate mode of delivery, whether written, oral, or multimodal, to present results. (TEKS 13H)

- Generate and clarify questions on a topic for formal and informal inquiry. (TEKS 13A)

- Develop a bibliography. (TEKS 13G)

- Use an appropriate mode of delivery, whether written, oral, or multimodal, to present results . (TEKS 13H)

- Understand credibility of primary and secondary sources. (TEKS 13D)

- Differentiate between paraphrasing and plagiarism when using source materials. (TEKS 13F)

20 Research Mini Lesson Ideas

Below are 20 research mini lessons for how to teach research skills to elementary students.

- Research and What it Looks Like

- The Steps in the Research Process

- Types of Resources

- Text Features in Websites

- Finding Resources on the Internet

- Finding Information in Non-Fiction Books

- Text Features in Non-Fiction Texts

- How to Use an Encyclopedia

- Conducting an Interview with an Expert

- Reading a Newspaper and Getting Information from it

- Previewing a Text for Research

- Evaluating a Resource to Determine if it is Reliable

- Citing Sources

- Facts vs. Opinions

- Taking notes

- Paraphrasing

- Summarizing

- Organizing Information

- Writing Like an Informational Writer

- Presenting Findings

What are the Research Steps for Elementary Students?

Here are the 4 steps of the research process for elementary students:

- Choose a topic.

- Search for information.

- Organize information.

- Share information.

Ideas for Elementary School Research Topics

Below are research topic ideas for elementary students.

Animal Research Topics for Elementary Students

1. ocean animals.

Oyster, tuna, cod, grouper, shrimp, barnacle, barracuda, shark, bass, whale, lobster, starfish, salmon, clam, conch, coral, crab, sea otter, dolphin, eel, seal, sea turtle, flounder, octopus, sea star, haddock, jellyfish, krill, manatee, marlin, seahorse, sea otter, sea cucumber, sea lion, sea urchin, stingray, squid, swordfish, and walrus

2. Land Animals

Aardvark, elephant, frog, dog, tortoise, ant, anteater, antelope, fox, rabbit, baboon, camel, badger, owl, bat, bear, beaver, bison, rhinoceros, spider, bobcat, buffalo, bumble bee, butterfly, cat, chameleon, cheetah, chicken, chipmunk, cockroach, cougar, cow, coyote, gorilla, deer, donkey, dragonfly, eagle, emu, ferret, flamingo, goat, goose, hedgehog, heron, hippopotamus, horse, hummingbird, hyena, iguana, jaguar, kangaroo, koala, lemur, leopard, lion, llama, meerkat, mongoose, monkey, moth, mouse, mule, panther, parrot, peacock, pelican, peacock, pheasant, pig, platypus, porcupine, possum, puma, quail, raccoon, rattlesnake, sheep, skunk, sloth, squirrel, swan, termite, tiger, turkey, vulture, walrus, weasel, wolf, woodpecker, yak, and zebra

3. Endangered Species

Bengal tiger, polar bear, Pacific walrus, Magellanic penguin, leatherback turtle, bluefish tuna, mountain gorilla, monarch butterfly, Javan rhinoceros, giant panda, amur leopard, sei whale, Asian elephant, sumatran elephant, pangolin, African wild dog, amur tiger, blue whale, bonobo, chimpanzee, dugong, Indus river dolphin, orangutan, red panda, sea lion, vaquita, whale shark, yangtze finless porpoise, North Atlantic right whale, and yellowfish tuna

Resources for Teaching Elementary Research Skills

Below are resources for teaching elementary student research skills.

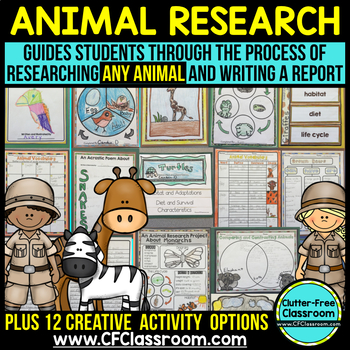

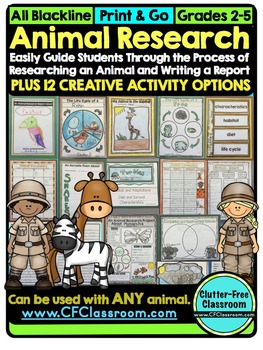

Animal Research Project

Learn more about the animal research project below!

What is the animal research project?

The animal research project is a printable and digital research project where students learn about any animal they choose. You can also choose the animals for them. The resource can be used over and over again all year long by just picking a new animal.

What grades is the animal research project appropriate for?

This resource includes tons of differentiated materials so it is appropriate for 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade students.

What is included in the animal research project?

The animal research project includes the following:

- teacher’s guide with tips and instructions to support you with your lesson planning and delivery

- parent communication letter to promote family involvement

- graphic organizers for brainstorming a topic, activating schema, taking notes, drafting writing

- research report publishing printables including a cover, writing templates and resource pages

- grading rubric so expectations are clear for students and grading is quick and easy for you

- research activities (KWL, can have are chart, compare/contrast Venn diagram, habitat map, vocabulary pages, illustration page, and life cycle charts)

- flipbook project printables to give an additional choice of how students can demonstrate their understanding

- flap book project printables to offer students another way to demonstrate their learning

- research poster to serve as an additional way to demonstrate student understanding

- poetry activities to offer students an alternative way to demonstrate their learning

- digital version so your students can access this resource in school or at home

4 Research Websites

Below are 4 research websites for elementary students.

- http://www.kidrex.org

- https://www.kiddle.co

- https://www.safesearchkids.com

- https://www.kidzsearch.com/boolify/

You might also like...

Thanksgiving Reading Comprehension Activities for 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Grade

Turkey Reading Activities for 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Grade

Bones Reading Comprehension Activities for 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Grade

Join the email club.

- CLUTTER-FREE TEACHER CLUB

- FACEBOOK GROUPS

- EMAIL COMMUNITY

- OUR TEACHER STORE

- ALL-ACCESS MEMBERSHIPS

- OUR TPT SHOP

- JODI & COMPANY

- TERMS OF USE

- Privacy Policy

Teaching Research Skills to K-12 Students in The Classroom

Research is at the core of knowledge. Nobody is born with an innate understanding of quantum physics. But through research , the knowledge can be obtained over time. That’s why teaching research skills to your students is crucial, especially during their early years.

But teaching research skills to students isn’t an easy task. Like a sport, it must be practiced in order to acquire the technique. Using these strategies, you can help your students develop safe and practical research skills to master the craft.

What Is Research?

By definition, it’s a systematic process that involves searching, collecting, and evaluating information to answer a question. Though the term is often associated with a formal method, research is also used informally in everyday life!

Whether you’re using it to write a thesis paper or to make a decision, all research follows a similar pattern.

- Choose a topic : Think about general topics of interest. Do some preliminary research to make sure there’s enough information available for you to work with and to explore subtopics within your subject.

- Develop a research question : Give your research a purpose; what are you hoping to solve or find?

- Collect data : Find sources related to your topic that will help answer your research questions.

- Evaluate your data : Dissect the sources you found. Determine if they’re credible and which are most relevant.

- Make your conclusion : Use your research to answer your question!

Why Do We Need It?

Research helps us solve problems. Trying to answer a theoretical question? Research. Looking to buy a new car? Research. Curious about trending fashion items? Research!

Sometimes it’s a conscious decision, like when writing an academic paper for school. Other times, we use research without even realizing it. If you’re trying to find a new place to eat in the area, your quick Google search of “food places near me” is research!

Whether you realize it or not, we use research multiple times a day, making it one of the most valuable lifelong skills to have. And it’s why — as educators —we should be teaching children research skills in their most primal years.

Teaching Research Skills to Elementary Students

In elementary school, children are just beginning their academic journeys. They are learning the essentials: reading, writing, and comprehension. But even before they have fully grasped these concepts, you can start framing their minds to practice research.

According to curriculum writer and former elementary school teacher, Amy Lemons , attention to detail is an essential component of research. Doing puzzles, matching games, and other memory exercises can help equip students with this quality before they can read or write.

Improving their attention to detail helps prepare them for the meticulous nature of research. Then, as their reading abilities develop, teachers can implement reading comprehension activities in their lesson plans to introduce other elements of research.

One of the best strategies for teaching research skills to elementary students is practicing reading comprehension . It forces them to interact with the text; if they come across a question they can’t answer, they’ll need to go back into the text to find the information they need.

Some activities could include completing compare/contrast charts, identifying facts or questioning the text, doing background research, and setting reading goals. Here are some ways you can use each activity:

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data

- Questioning the text : If students are unsure which are facts/not facts, encourage them to go back into the text to find their answers.

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data; Step 5, make your conclusion

- How it translates : Step 1, choose your topic

- How it translates : Step 2, develop a research question; Step 5, make your conclusion

Resources for Elementary Research

If you have access to laptops or tablets in the classroom, there are some free tools available through Pennsylvania’s POWER Kids to help with reading comprehension. Scholastic’s BookFlix and TrueFlix are 2 helpful resources that prompt readers with questions before, after, and while they read.

- BookFlix : A resource for students who are still new to reading. Students will follow along as a book is read aloud. As they listen or read, they will be prodded to answer questions and play interactive games to test and strengthen their understanding.

- TrueFlix : A resource for students who are proficient in reading. In TrueFlix, students explore nonfiction topics. It’s less interactive than BookFlix because it doesn’t prompt the reader with games or questions as they read. (There are still options to watch a video or listen to the text if needed!)

Teaching Research Skills to Middle School Students

By middle school, the concept of research should be familiar to students. The focus during this stage should be on credibility . As students begin to conduct research on their own, it’s important that they know how to determine if a source is trustworthy.

Before the internet, encyclopedias were the main tool that people used for research. Now, the internet is our first (and sometimes only) way of looking information up.

Unlike encyclopedias which can be trusted, students must be wary of pulling information offline. The internet is flooded with unreliable and deceptive information. If they aren’t careful, they could end up using a source that has inaccurate information!

How To Know If A Source Is Credible

In general, credible sources are going to come from online encyclopedias, academic journals, industry journals, and/or an academic database. If you come across an article that isn’t from one of those options, there are details that you can look for to determine if it can be trusted.

- The author: Is the author an expert in their field? Do they write for a respected publication? If the answer is no, it may be good to explore other sources.

- Citations: Does the article list its sources? Are the sources from other credible sites like encyclopedias, databases, or journals? No list of sources (or credible links) within the text is usually a red flag.

- Date: When was the article published? Is the information fresh or out-of-date? It depends on your topic, but a good rule of thumb is to look for sources that were published no later than 7-10 years ago. (The earlier the better!)

- Bias: Is the author objective? If a source is biased, it loses credibility.

An easy way to remember what to look for is to utilize the CRAAP test . It stands for C urrency (date), R elevance (bias), A uthority (author), A ccuracy (citations), and P urpose (bias). They’re noted differently, but each word in this acronym is one of the details noted above.

If your students can remember the CRAAP test, they will be able to determine if they’ve found a good source.

Resources for Middle School Research

To help middle school researchers find reliable sources, the database Gale is a good starting point. It has many components, each accessible on POWER Library’s site. Gale Litfinder , Gale E-books , or Gale Middle School are just a few of the many resources within Gale for middle school students.

Teaching Research Skills To High Schoolers

The goal is that research becomes intuitive as students enter high school. With so much exposure and practice over the years, the hope is that they will feel comfortable using it in a formal, academic setting.

In that case, the emphasis should be on expanding methodology and citing correctly; other facets of a thesis paper that students will have to use in college. Common examples are annotated bibliographies, literature reviews, and works cited/reference pages.

- Annotated bibliography : This is a sheet that lists the sources that were used to conduct research. To qualify as annotated , each source must be accompanied by a short summary or evaluation.

- Literature review : A literature review takes the sources from the annotated bibliography and synthesizes the information in writing.

- Works cited/reference pages : The page at the end of a research paper that lists the sources that were directly cited or referenced within the paper.

Resources for High School Research

Many of the Gale resources listed for middle school research can also be used for high school research. The main difference is that there is a resource specific to older students: Gale High School .

If you’re looking for some more resources to aid in the research process, POWER Library’s e-resources page allows you to browse by grade level and subject. Take a look at our previous blog post to see which additional databases we recommend.

Visit POWER Library’s list of e-resources to start your research!

- Research Skills

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

Please note, I am no longer blogging and this post hasn’t updated since April 2020.

For a number of years, Seth Godin has been talking about the need to “ connect the dots” rather than “collect the dots” . That is, rather than memorising information, students must be able to learn how to solve new problems, see patterns, and combine multiple perspectives.

Solid research skills underpin this. Having the fluency to find and use information successfully is an essential skill for life and work.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever.

You might be wondering how you can fit teaching research skills into a busy curriculum? There aren’t enough hours in the day! The good news is, there are so many mini-lessons you can do to build students’ skills over time.

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!).

Learn More About The Research Process

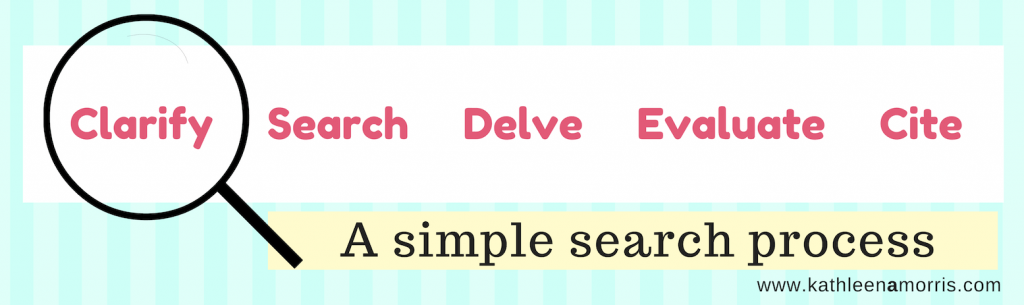

I have a popular post called Teach Students How To Research Online In 5 Steps. It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks.

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Notes about the 50 research activities:

- These ideas can be adapted for different age groups from middle primary/elementary to senior high school.

- Many of these ideas can be repeated throughout the year.

- Depending on the age of your students, you can decide whether the activity will be more teacher or student led. Some activities suggest coming up with a list of words, questions, or phrases. Teachers of younger students could generate these themselves.

- Depending on how much time you have, many of the activities can be either quickly modelled by the teacher, or extended to an hour-long lesson.

- Some of the activities could fit into more than one category.

- Looking for simple articles for younger students for some of the activities? Try DOGO News or Time for Kids . Newsela is also a great resource but you do need to sign up for free account.

- Why not try a few activities in a staff meeting? Everyone can always brush up on their own research skills!

- Choose a topic (e.g. koalas, basketball, Mount Everest) . Write as many questions as you can think of relating to that topic.

- Make a mindmap of a topic you’re currently learning about. This could be either on paper or using an online tool like Bubbl.us .

- Read a short book or article. Make a list of 5 words from the text that you don’t totally understand. Look up the meaning of the words in a dictionary (online or paper).

- Look at a printed or digital copy of a short article with the title removed. Come up with as many different titles as possible that would fit the article.

- Come up with a list of 5 different questions you could type into Google (e.g. Which country in Asia has the largest population?) Circle the keywords in each question.

- Write down 10 words to describe a person, place, or topic. Come up with synonyms for these words using a tool like Thesaurus.com .

- Write pairs of synonyms on post-it notes (this could be done by the teacher or students). Each student in the class has one post-it note and walks around the classroom to find the person with the synonym to their word.

- Explore how to search Google using your voice (i.e. click/tap on the microphone in the Google search box or on your phone/tablet keyboard) . List the pros and cons of using voice and text to search.

- Open two different search engines in your browser such as Google and Bing. Type in a query and compare the results. Do all search engines work exactly the same?

- Have students work in pairs to try out a different search engine (there are 11 listed here ). Report back to the class on the pros and cons.

- Think of something you’re curious about, (e.g. What endangered animals live in the Amazon Rainforest?). Open Google in two tabs. In one search, type in one or two keywords ( e.g. Amazon Rainforest) . In the other search type in multiple relevant keywords (e.g. endangered animals Amazon rainforest). Compare the results. Discuss the importance of being specific.

- Similar to above, try two different searches where one phrase is in quotation marks and the other is not. For example, Origin of “raining cats and dogs” and Origin of raining cats and dogs . Discuss the difference that using quotation marks makes (It tells Google to search for the precise keywords in order.)

- Try writing a question in Google with a few minor spelling mistakes. What happens? What happens if you add or leave out punctuation ?

- Try the AGoogleADay.com daily search challenges from Google. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

- Explore how Google uses autocomplete to suggest searches quickly. Try it out by typing in various queries (e.g. How to draw… or What is the tallest…). Discuss how these suggestions come about, how to use them, and whether they’re usually helpful.

- Watch this video from Code.org to learn more about how search works .

- Take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “ instant searches ”. Try one to try out. Perhaps each student could be assigned one to try and share with the class.

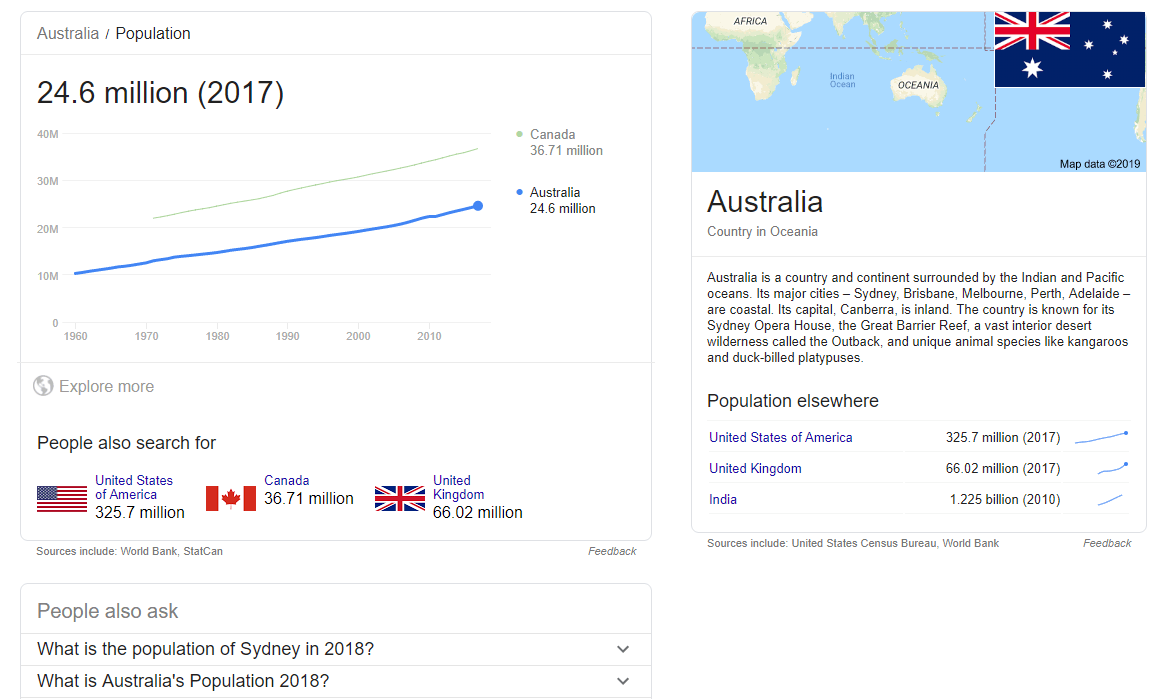

- Experiment with typing some questions into Google that have a clear answer (e.g. “What is a parallelogram?” or “What is the highest mountain in the world?” or “What is the population of Australia?”). Look at the different ways the answers are displayed instantly within the search results — dictionary definitions, image cards, graphs etc.

- Watch the video How Does Google Know Everything About Me? by Scientific American. Discuss the PageRank algorithm and how Google uses your data to customise search results.

- Brainstorm a list of popular domains (e.g. .com, .com.au, or your country’s domain) . Discuss if any domains might be more reliable than others and why (e.g. .gov or .edu) .

- Discuss (or research) ways to open Google search results in a new tab to save your original search results (i.e. right-click > open link in new tab or press control/command and click the link).

- Try out a few Google searches (perhaps start with things like “car service” “cat food” or “fresh flowers”). A re there advertisements within the results? Discuss where these appear and how to spot them.

- Look at ways to filter search results by using the tabs at the top of the page in Google (i.e. news, images, shopping, maps, videos etc.). Do the same filters appear for all Google searches? Try out a few different searches and see.

- Type a question into Google and look for the “People also ask” and “Searches related to…” sections. Discuss how these could be useful. When should you use them or ignore them so you don’t go off on an irrelevant tangent? Is the information in the drop-down section under “People also ask” always the best?

- Often, more current search results are more useful. Click on “tools” under the Google search box and then “any time” and your time frame of choice such as “Past month” or “Past year”.

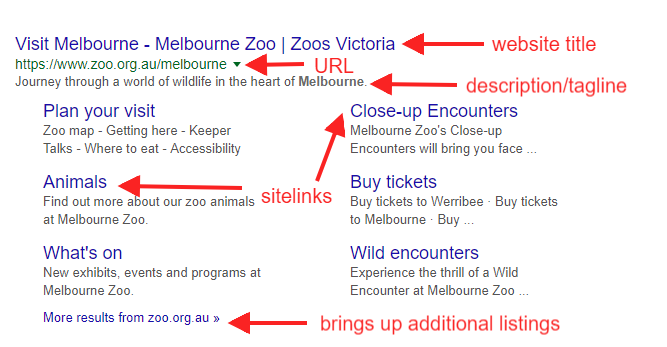

- Have students annotate their own “anatomy of a search result” example like the one I made below. Explore the different ways search results display; some have more details like sitelinks and some do not.

- Find two articles on a news topic from different publications. Or find a news article and an opinion piece on the same topic. Make a Venn diagram comparing the similarities and differences.

- Choose a graph, map, or chart from The New York Times’ What’s Going On In This Graph series . Have a whole class or small group discussion about the data.

- Look at images stripped of their captions on What’s Going On In This Picture? by The New York Times. Discuss the images in pairs or small groups. What can you tell?

- Explore a website together as a class or in pairs — perhaps a news website. Identify all the advertisements .

- Have a look at a fake website either as a whole class or in pairs/small groups. See if students can spot that these sites are not real. Discuss the fact that you can’t believe everything that’s online. Get started with these four examples of fake websites from Eric Curts.

- Give students a copy of my website evaluation flowchart to analyse and then discuss as a class. Read more about the flowchart in this post.

- As a class, look at a prompt from Mike Caulfield’s Four Moves . Either together or in small groups, have students fact check the prompts on the site. This resource explains more about the fact checking process. Note: some of these prompts are not suitable for younger students.

- Practice skim reading — give students one minute to read a short article. Ask them to discuss what stood out to them. Headings? Bold words? Quotes? Then give students ten minutes to read the same article and discuss deep reading.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

- Watch the video Citation for Beginners for an introduction to citation. Discuss the key points to remember.

- Look up the definition of plagiarism using a variety of sources (dictionary, video, Wikipedia etc.). Create a definition as a class.

- Find an interesting video on YouTube (perhaps a “life hack” video) and write a brief summary in your own words.

- Have students pair up and tell each other about their weekend. Then have the listener try to verbalise or write their friend’s recount in their own words. Discuss how accurate this was.

- Read the class a copy of a well known fairy tale. Have them write a short summary in their own words. Compare the versions that different students come up with.

- Try out MyBib — a handy free online tool without ads that helps you create citations quickly and easily.

- Give primary/elementary students a copy of Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Citation that matches their grade level (the guide covers grades 1 to 6). Choose one form of citation and create some examples as a class (e.g. a website or a book).

- Make a list of things that are okay and not okay to do when researching, e.g. copy text from a website, use any image from Google images, paraphrase in your own words and cite your source, add a short quote and cite the source.

- Have students read a short article and then come up with a summary that would be considered plagiarism and one that would not be considered plagiarism. These could be shared with the class and the students asked to decide which one shows an example of plagiarism .

- Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising . They could create a Venn diagram that compares the two.

- Write a list of statements on the board that might be true or false ( e.g. The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia. The rhinoceros is the largest land animal in the world. The current marathon world record is 2 hours, 7 minutes). Have students research these statements and decide whether they’re true or false by sharing their citations.

Staying Organised

- Make a list of different ways you can take notes while researching — Google Docs, Google Keep, pen and paper etc. Discuss the pros and cons of each method.

- Learn the keyboard shortcuts to help manage tabs (e.g. open new tab, reopen closed tab, go to next tab etc.). Perhaps students could all try out the shortcuts and share their favourite one with the class.

- Find a collection of resources on a topic and add them to a Wakelet .

- Listen to a short podcast or watch a brief video on a certain topic and sketchnote ideas. Sylvia Duckworth has some great tips about live sketchnoting

- Learn how to use split screen to have one window open with your research, and another open with your notes (e.g. a Google spreadsheet, Google Doc, Microsoft Word or OneNote etc.) .

All teachers know it’s important to teach students to research well. Investing time in this process will also pay off throughout the year and the years to come. Students will be able to focus on analysing and synthesizing information, rather than the mechanics of the research process.

By trying out as many of these mini-lessons as possible throughout the year, you’ll be really helping your students to thrive in all areas of school, work, and life.

Also remember to model your own searches explicitly during class time. Talk out loud as you look things up and ask students for input. Learning together is the way to go!

You Might Also Enjoy Reading:

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

Five Tips for Teaching Students How to Research and Filter Information

Typing Tips: The How and Why of Teaching Students Keyboarding Skills

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

10 Replies to “50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills”

Loving these ideas, thank you

This list is amazing. Thank you so much!

So glad it’s helpful, Alex! 🙂

Hi I am a student who really needed some help on how to reasearch thanks for the help.

So glad it helped! 🙂

seriously seriously grateful for your post. 🙂

So glad it’s helpful! Makes my day 🙂

How do you get the 50 mini lessons. I got the free one but am interested in the full version.

Hi Tracey, The link to the PDF with the 50 mini lessons is in the post. Here it is . Check out this post if you need more advice on teaching students how to research online. Hope that helps! Kathleen

Best wishes to you as you face your health battler. Hoping you’ve come out stronger and healthier from it. Your website is so helpful.

Comments are closed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Jan 24, 2023 · Teaching academically honest research skills helps first graders learn how to collect, organize, and interpret information.

Teaching research skills to elementary students takes the entire year. Start with short, teacher-generated activities. Continue with guided subject-area projects. Finally, your students will be ready for independent research.

Aug 1, 2024 · As a school librarian, I've seen firsthand how crucial research skills are for young learners. In this guide, we'll explore effective strategies for teaching research to elementary students, empowering them to become confident and capable information seekers.

Learn how to teach research skills to elementary students in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th grade in this Clutter-Free Classroom blog post.

One of the best strategies for teaching research skills to elementary students is practicing reading comprehension. It forces them to interact with the text; if they come across a question they can’t answer, they’ll need to go back into the text to find the information they need.

Feb 26, 2019 · Learn how to teach research skills to primary students, middle school students, or high school students. 50 activities that could be done in just a few minutes a day. Lots of Google search tips and research tips for kids and teachers.