Advertisement

Supported by

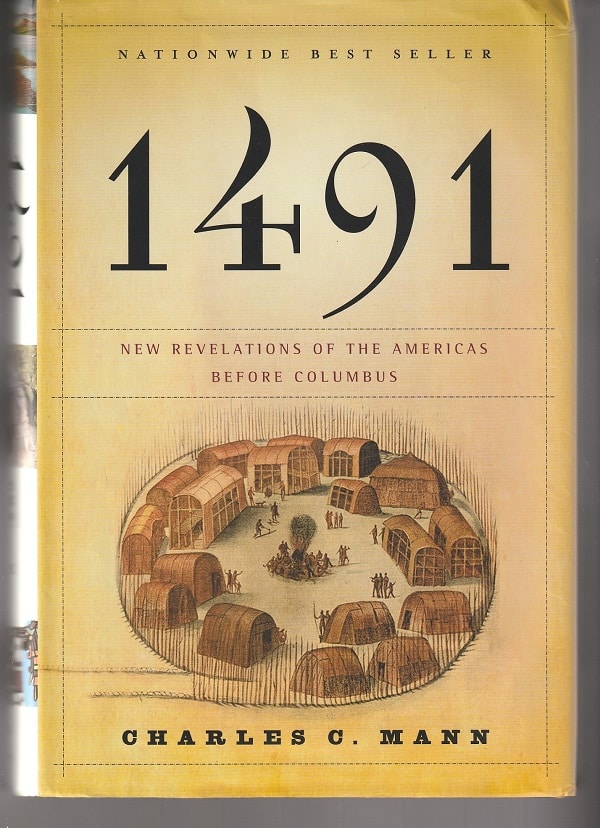

'1491': Vanished Americans

- Share full article

By Kevin Baker

- Oct. 9, 2005

New Revelations of the Americas

Before Columbus.

By Charles C. Mann.

Illustrated. 462 pp.

Alfred A. Knopf. $30.

MOST of us know, or think we know, what the first Europeans encountered when they began their formal invasion of the Americas in 1492: a pristine world of overwhelming natural abundance and precious few people; a hemisphere where -- save perhaps for the Aztec and Mayan civilizations of Central America and the Incan state in Peru -- human beings indeed trod lightly upon the earth. Small wonder that, right up to the present day, American Indians have usually been presented as either underachieving metahippies, tree-hugging saints or some combination of the two.

The trouble with all such stereotypes, as Charles C. Mann points out in his marvelous new book, "1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus," is that they are essentially dehumanizing. For cultural reasons of their own, Europeans and white Americans have "implicitly depicted Indians as people who never changed their environment from its original wild state. Because history is change, they were people without history."

Mann, a science journalist and co-author of four previous books on subjects ranging from aspirin to physics to the Internet, provides an important corrective -- a sweeping portrait of human life in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus. This would be a formidable task under any circumstance, and it is complicated by the fact that so much of the deep American past is embroiled in vituperative political and scientific controversies.

Nearly everything about the Indians is currently a matter of contention. There is little or no agreement about when their ancestors first came to the Americas and where they came from; how many there were, how and where they lived and why they were not more effective in resisting the European invasion. New archaeological discoveries and interpretations of Indian materials are constantly altering the historical record, and every debate comes equipped with its own bevy of archaeologists, anthropologists and other social scientists tossing around personal invective with the abandon of Rudy Giuliani on a bad day.

Mann navigates adroitly through the controversies. He approaches each in the best scientific tradition, carefully sifting the evidence, never jumping to hasty conclusions, giving everyone a fair hearing -- the experts and the amateurs; the accounts of the Indians and their conquerors. And rarely is he less than enthralling. A remarkably engaging writer, he lucidly explains the significance of everything from haplogroups to glottochronology to landraces. He offers amusing asides to some of his adventures across the hemisphere during the course of his research, but unlike so many contemporary journalists, he never lets his personal experiences overwhelm his subject.

Instead, Mann builds his story around what we want to know -- the "Frequently Asked Questions," as he heads one chapter. He moves nimbly back and forth from the earliest prehistoric humans in the Americas to the Pilgrims' first encounter with the Indian they (mistakenly) called "Squanto"; from the villages of the Amazon rain forests to Cahokia, near modern St. Louis, the sole, long-vanished city of the North American Mound Builders; from the cultivation of maize to why it was that the Incas apparently developed the wheel but never used it as anything but a child's toy.

Mann remains resolutely agnostic on some of the fiercest debates. What he is most interested in showing us is how American Indians -- like all other human beings -- were intensely involved in shaping the world they lived in. He is sure that "many though not all Indians were superbly active land managers -- they did not live lightly on the land." Just how they did live, so long uninfluenced by the vast majority of the world's population in Africa and Eurasia, forms the bulk of his fascinating narrative.

What emerges is an epic story, with a subtly altered tragedy at its heart. For all the European depredations in the Americas, the work of conquest was largely accomplished for them by their microbes, even before the white men arrived in any great numbers. The diseases brought along by the very first unwitting Spanish conquistadors, and probably by English fishermen working the New England coast, very likely triggered one of the greatest catastrophes in human history. Before the 16th century, there may have been as many as 90 million to 112 million people living in the Americas -- people who could be as different from each other "as Turks and Swedes," but who had cumulatively developed an incredible range of natural environments, from seeding the Amazon Basin with fruit trees to terracing the mountains of Peru. (Even the term "New World" may be a misnomer; it is possible that the world's first city was in South America.)

Then, disaster. According to some estimates, as much as 95 percent of the Indians may have died almost immediately on contact with various European diseases, particularly smallpox. That would have amounted to about one-fifth of the world's total population at the time, a level of destruction unequaled before or since. The exact numbers, like everything else, are in dispute, but it is clear that these plagues wreaked havoc on traditional Indian societies. European misreadings of America should not be attributed wholly to ethnic arrogance. The "savages" most of the colonists saw, without ever realizing it, were usually the traumatized, destitute survivors of ancient and intricate civilizations that had collapsed almost overnight. Even the superabundant "nature" the Europeans inherited had been largely put in place by these now absent gardeners, and had run wild only after they had ceased to cull and harvest it.

In the end, the loss to us all was incalculable. As Mann writes, "Having grown separately for millennia, the Americas were a boundless sea of novel ideas, dreams, stories, philosophies, religions, moralities, discoveries and all the other products of the mind. Few things are more sublime or characteristically human than the cross-fertilization of cultures. The simple discovery by Europe of the existence of the Americas caused an intellectual ferment. How much grander would have been the tumult if Indian societies had survived in full splendor!"

Kevin Baker is the author of the forthcoming historical novel "Strivers Row."

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

10 Best Books of 2024: The staff of The New York Times Book Review has chosen the year’s top fiction and nonfiction . For even more great reads, take a spin through all 100 Notable Books of 2024 .

Falling in Love With a Poem: “Romantic Poet,” by Diane Seuss, is one of the best things that our critic A.O. Scott read (and reread) this year .

A Book Tour With a Side of Fried Rice: Curtis Chin’s memoir, “Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant,” celebrates the cuisine and community of his youth . Now he’s paying it forward.

Cormac McCarthy’s Secret: Revelations about a relationship between the author and a girl who was 16 when they met shocked readers, but not scholars of his work. Now there’s a debate about how much she influenced his writing .

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

NEW REVELATIONS OF THE AMERICAS BEFORE COLUMBUS

by Charles C. Mann ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 12, 2005

An excellent, and highly accessible, survey of America’s past: a worthy companion to Jake Page’s In the Hands of the Great...

Unless you’re an anthropologist, it’s likely that everything you know about American prehistory is wrong. Science journalist Mann’s survey of the current knowledge is a bracing corrective.

Historians once thought that prehistoric Indian peoples somehow lived outside of history, adrift and directionless, “passive recipients of whatever windfalls or disasters happenstance put in their way”; that view was central to the myth of the noble savage. In fact, writes Mann ( Noah’s Choice , with Mark L. Plummer, 1995), Native Americans were as active in shaping their environments as anyone else. They built great and wealthy cities; they lived, for the most part, on farms; and their home continents “were immeasurably busier, more diverse, and more populous than researchers had previously imagined.” In defending this view, Mann visits several thriving controversies in the historic/prehistoric record. One is the question of pre-contact demographics: old-school scholars had long advanced the idea that there were only a few million Native Americans at the time of the Columbian arrival, whereas revisionists in the 1960s posited that there were eight million on the island of Hispaniola alone, a figure punctured by revisionists of revisionism, now beset by Native American activists for the political incorrectness of adjusting the census. Another controversy is the chronology of human presence in the Americas: the old date of 12,000 b.c., courtesy of the Bering Land Bridge in Alaska, no longer cuts it. Other arguments center on the nature of Native American societies such as the Aztec and Inca, the latter of whom built a great empire that, defying Western notions of logic, had no market component. Mann addresses each controversy with care, according the old-timers their due while making it clear that his sympathies lie, in the main, with the rising generation. He closes with a provocative thesis: namely, that the present worldwide movement toward democracy owes not to Locke or Newtonian physics, but to Indians, “living, breathing role models of human liberty.”

Pub Date: Aug. 12, 2005

ISBN: 1-4000-4006-X

Page Count: 480

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: June 1, 2005

HISTORY | FIRST/NATIVE NATIONS | GENERAL HISTORY

Share your opinion of this book

More by Charles C. Mann

BOOK REVIEW

by Charles C. Mann

by Charles C. Mann ; adapted by Rebecca Stefoff

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2017

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

National Book Award Finalist

KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON

The osage murders and the birth of the fbi.

by David Grann ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 18, 2017

Dogged original research and superb narrative skills come together in this gripping account of pitiless evil.

Greed, depravity, and serial murder in 1920s Oklahoma.

During that time, enrolled members of the Osage Indian nation were among the wealthiest people per capita in the world. The rich oil fields beneath their reservation brought millions of dollars into the tribe annually, distributed to tribal members holding "headrights" that could not be bought or sold but only inherited. This vast wealth attracted the attention of unscrupulous whites who found ways to divert it to themselves by marrying Osage women or by having Osage declared legally incompetent so the whites could fleece them through the administration of their estates. For some, however, these deceptive tactics were not enough, and a plague of violent death—by shooting, poison, orchestrated automobile accident, and bombing—began to decimate the Osage in what they came to call the "Reign of Terror." Corrupt and incompetent law enforcement and judicial systems ensured that the perpetrators were never found or punished until the young J. Edgar Hoover saw cracking these cases as a means of burnishing the reputation of the newly professionalized FBI. Bestselling New Yorker staff writer Grann ( The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: Tales of Murder, Madness, and Obsession , 2010, etc.) follows Special Agent Tom White and his assistants as they track the killers of one extended Osage family through a closed local culture of greed, bigotry, and lies in pursuit of protection for the survivors and justice for the dead. But he doesn't stop there; relying almost entirely on primary and unpublished sources, the author goes on to expose a web of conspiracy and corruption that extended far wider than even the FBI ever suspected. This page-turner surges forward with the pacing of a true-crime thriller, elevated by Grann's crisp and evocative prose and enhanced by dozens of period photographs.

Pub Date: April 18, 2017

ISBN: 978-0-385-53424-6

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: Feb. 1, 2017

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 15, 2017

GENERAL HISTORY | TRUE CRIME | UNITED STATES | FIRST/NATIVE NATIONS | HISTORY

More by David Grann

by David Grann

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

by Elie Wiesel & translated by Marion Wiesel ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 16, 2006

The author's youthfulness helps to assure the inevitable comparison with the Anne Frank diary although over and above the...

Elie Wiesel spent his early years in a small Transylvanian town as one of four children.

He was the only one of the family to survive what Francois Maurois, in his introduction, calls the "human holocaust" of the persecution of the Jews, which began with the restrictions, the singularization of the yellow star, the enclosure within the ghetto, and went on to the mass deportations to the ovens of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. There are unforgettable and horrifying scenes here in this spare and sombre memoir of this experience of the hanging of a child, of his first farewell with his father who leaves him an inheritance of a knife and a spoon, and of his last goodbye at Buchenwald his father's corpse is already cold let alone the long months of survival under unconscionable conditions.

Pub Date: Jan. 16, 2006

ISBN: 0374500010

Page Count: 120

Publisher: Hill & Wang

Review Posted Online: Oct. 7, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2006

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | HOLOCAUST | HISTORY | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL HISTORY

More by Elie Wiesel

by Elie Wiesel ; edited by Alan Rosen

by Elie Wiesel ; illustrated by Mark Podwal

by Elie Wiesel ; translated by Marion Wiesel

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

Charles c. mann.

In this groundbreaking work of science, history, and archaeology, Charles C. Mann radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus in 1492. Contrary to what so many Americans learn in school, the pre-Columbian Indians were not sparsely settled in a pristine wilderness; rather, there were huge numbers of Indians who actively molded and influenced the land around them. The astonishing Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had running water and immaculately clean streets, and was larger than any contemporary European city. Mexican cultures created corn in a specialized breeding process that it has been called man’s first feat of genetic engineering. Indeed, Indians were not living lightly on the land but were landscaping and manipulating their world in ways that we are only now beginning to understand. Challenging and surprising, this a transformative new look at a rich and fascinating world we only thought we knew.

563 pages, Paperback

First published August 9, 2005

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

- Access our Top 20 Books of 2024! Access

Summary and Reviews of 1491 by Charles Mann

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

- BookBrowse Review:

- Critics' Consensus ( 7 ) :

- Readers' Rating ( 8 ):

- First Published:

- Aug 1, 2005, 480 pages

- Oct 2006, 528 pages

- History, Current Affairs and Religion

- 17th Century or Earlier

- Nature & Environment

- Publication Information

- Write a Review

- Buy This Book Amazon Bookshop.org

About This Book

- Book Club Questions

Book Summary

A groundbreaking study that radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans in 1492. Traditionally, Americans learned in school that the ancestors of the people who inhabited the Western Hemisphere at the time of Columbus’s landing had crossed the Bering Strait twelve thousand years ago; existed mainly in small, nomadic bands; and lived so lightly on the land that the Americas was, for all practical purposes, still a vast wilderness. But as Charles C. Mann now makes clear, archaeologists and anthropologists have spent the last thirty years proving these and many other long-held assumptions wrong. In a book that startles and persuades, Mann reveals how a new generation of researchers equipped with novel scientific techniques came to previously unheard-of conclusions. Among them:

- In 1491 there were probably more people living in the Americas than in Europe.

- Certain cities–such as Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital–were far greater in population than any contemporary European city. Furthermore, Tenochtitlán, unlike any capital in Europe at that time, had running water, beautiful botanical gardens, and immaculately clean streets.

- The earliest cities in the Western Hemisphere were thriving before the Egyptians built the great pyramids.

- Pre-Columbian Indians in Mexico developed corn by a breeding process so sophisticated that the journal Science recently described it as "man’s first, and perhaps the greatest, feat of genetic engineering."

- Amazonian Indians learned how to farm the rain forest without destroying it–a process scientists are studying today in the hope of regaining this lost knowledge.

- Native Americans transformed their land so completely that Europeans arrived in a hemisphere already massively "landscaped" by human beings.

Mann sheds clarifying light on the methods used to arrive at these new visions of the pre-Columbian Americas and how they have affected our understanding of our history and our thinking about the environment. His book is an exciting and learned account of scientific inquiry and revelation.

Why Billington Survived The Friendly Indian On March 22, 1621, an official Native American delegation walked through what is now southern New England to negotiate with a group of foreigners who had taken over a recently deserted Indian settlement. At the head of the party was an uneasy triumvirate: Massasoit, the sachem (political-military leader) of the Wampanoag confederation, a loose coalition of several dozen villages that controlled most of what is now southeastern Massachusetts; Samoset, sachem of an allied group to the north; and Tisquantum, a distrusted captive, whom Massasoit had reluctantly brought along as an interpreter. Massasoit was an adroit politician, but the dilemma he faced would have tested Machiavelli. About five years before, most of his subjects had fallen before a terrible calamity. Whole villages had been ...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews, bookbrowse review.

In a book that startles and persuades, Mann reveals how a new generation of researchers equipped with novel scientific techniques came to previously unheard-of conclusions... continued

Full Review (286 words) This review is available to non-members for a limited time. For full access, become a member today .

(Reviewed by BookBrowse Review Team ).

Write your own review!

Beyond the Book

The article that formed the basis for this book was originally published in The Atlantic Monthly in 2002. If, after reading the extensive book excerpt and author interview at BookBrowse, you want to read more you can read the Atlantic Monthly article here . Also of interest is an extensive review in the Washington Post Book World written by Alan Taylor, the author of American Colonies , and a professor of history at the University of California at Davis. Did you know? In response to the frequently asked question, "why do you have a 'pretentious' C in your name?" Charles C Mann replies, "I get asked about this a lot, occasionally in exactly those words. The answer is not very interesting. I am named after ...

This "beyond the book" feature is available to non-members for a limited time. Join today for full access.

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked 1491, try these:

On Savage Shores

by Caroline Dodds Pennock

Published 2024

About this book

A landmark work of narrative history that shatters our previous Eurocentric understanding of the Age of Discovery by telling the story of the Indigenous Americans who journeyed across the Atlantic to Europe after 1492

In Search of a Kingdom

by Laurence Bergreen

Published 2022

More by this author

In this grand and thrilling narrative, the acclaimed biographer of Magellan, Columbus, and Marco Polo brings alive the singular life and adventures of Sir Francis Drake, the pirate/explorer/admiral whose mastery of the seas during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I changed the course of history.

Books with similar themes

BookBrowse Book Club

Who Said...

When an old man dies, a library burns to the ground.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Big Holiday Wordplay 2024

Book review: “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” by Charles C. Mann

Prior to publishing 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus in 2006, Charles C. Mann had co-authored a few books on science and technology. But he had specialized in writing magazine pieces on scientific subjects for such publications as Fortune, Smithsonian, Technology Review, Vanity Fair, Science, the Atlantic Monthly and Wired .

Indeed, at many points in 1491 , Mann describes encounters he had with archeologists and visits he made to ancient sites while carrying out magazine assignments.

So, it’s not very surprising that his book has the feel of several long magazine stories packaged together under a single thesis.

That thesis could be summarized in a question that Mann read in an article in a technical journal in 1992:

“What was the New World like at the time of Columbus?”

Nomadic Indians and virgin landscapes

In other words, when Christopher Columbus and his crews became the first Europeans to record a visit to the Western Hemisphere, who were the Indians that they found? How many Indians were there in what became known as North America and South America? What were the cultures and civilizations of the Indians? What was the relationship of the Indians to their landscapes? How long had they been there?

For much of the past five hundred years, the answers to those questions, as presented in textbooks and general histories, were that, at the time Columbus arrived, Indians had loosely settled the two continents and, with a few exceptions, lived nomadic lives, hunting and gathering and living off the bounty of the land.

And the land they lived on was primeval Nature, a virgin landscape, as pristine as when the Indians arrived. It remained pure because the Indians were so technologically primitive and used the land so lightly.

It was that primordial wildness that, starting in the mid-20 th century, environmentalists asserted was the ideal — an ideal to use as the template in protecting the few “virgin” areas left and in reconstructing such wildernesses.

Mann, though, knew — and found out even more as he researched — that those ideas were very much out of date. So, he wrote his book.

Demography, origins and ecology

At the beginning of 1491 , Mann alerts the reader that his book isn’t a systematic, chronological account of the Western Hemisphere’s cultural and social development before Europeans arrived. Such a book, he comments, would need to be so vast in scope in terms of space and time that it would be impossible to write.

Nor, he writes, is it a “full intellectual history of the recent changes in perspective among the anthropologists, archeologists, ecologists, geographers, and historians who study the first Americans,” a similarly impossible task since so many new ideas “are still rippling outward in too many directions” to be contained in a single work.

“Instead, this book explores what I believe to be the three main foci of the new findings: Indian demography (Part I), Indian origins (Part II) and Indian ecology (Part III). Because so many different societies illustrate these points in such different ways, I could not possibly be comprehensive. Instead, I chose my examples from cultures that are among the best documented, or have drawn the most recent attention, or just seemed the most intriguing.”

“A sweeping portrait”

After reading 1491 , I disagree with Mann that his approach was the only viable one. And I think he made a mistake to write the book he wrote.

Of course, what do I know?

1491 was and remains a bestseller, called “a sweeping portrait of human life in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus” by the New York Times and “concise and brilliantly entertaining” by the Los Angeles Times . I must be barking up the wrong tree. After all, as the century-old song says, 50 million Frenchmen can’t be wrong.

Well, for what it’s worth, I think Mann’s book was and remains a bestseller because of his magazine-article approach to the stories that make up his chapters and sections of chapters.

Like many a magazine writer, Mann puts himself in the story. Here he is at this ruin watching Archeologist A ever-so-carefully digging up a piece of pottery. Here he is in an office at Harvard or Chicago’s Field Museum or Stanford interviewing Anthropologist B or Historian C.

Also, like many a magazine story, the tales Mann tells often have to do with disputes between one set of experts and another set of experts. This gives these accounts a narrative tension — Is this one right? Or maybe this one?

How iffy or solid?

Having proclaimed comprehensiveness to be impossible, Mann gives himself freedom to tell stories all over the hemispheric map from all up and down the millenniums.

Conceivably, the result could have been an impressionistic account of the state of research into the world and lives of ancient Indians. It wouldn’t have been comprehensive, but it might have given an overview that would stress what seems pretty clear rather than emphasizing the debates over what’s not clear.

Mann, though, doesn’t present an overview. Instead, he layers this story on that story on another story in what, to me, seemed to be a hodge-podge of dates and details and personalities. This, I think, is due to his magazine-article approach to his text.

The stuff with a story fits, and the stuff without a story is left out. The only framework is a vaguely delineated subject area, such as Indian demography. The goal is to inform and entertain, with the main emphasis on entertainment.

I felt inundated and overwhelmed by all this data, much of it in question, presented in anecdote after scene after debate after speculation. From page to page, I couldn’t tell how iffy or solid this stuff was.

It seems pretty clear — and Mann’s accounts of bad old theories reinforce this — that the descriptions by present-day scholars about Indian life five hundred or two thousand or however many years ago are based on an attempt to read of the evidence.

In some cases, there is actually something to read written in a language that can be deciphered although that involves a lot of guesswork. Even more guesswork comes into play when experts are trying to envision what life was like for specific Indians at some specific time in the far distant past based on ruins and pottery and pollen counts.

It’s detective work. Here, the focus is on the detecting, on the story of the detecting, rather than stepping back and giving an analysis of a pattern of discovery. I would have preferred a book that involved both detective stories and analysis.

Key findings

The key findings of Mann’s book are fairly simple in the broadest sense:

- Modern research seems to indicate pretty clearly that there were a lot more Indians in the Western Hemisphere in 1491 that previous generations of researchers had believed. Exactly how many is widely debated.

- Modern research seems to indicate pretty clearly that Indians have been on the two continents a lot longer than previous generations of researchers had believed. Exactly how many is widely debated.

- Modern research seems to indicate pretty clearly that Indians did much to shape, manipulate, rearrange and tinker with the natural world — to terraform, to suit their needs — than previous generations of researchers had been able to envision.

The moral dimension

These are striking insights, and they raise many questions about the collision of Europeans with Indians after the arrival of Columbus, such as the deaths of large numbers of Indians who had no means to fight off the diseases that Europeans — innocently — brought with them.

Innocent to the extent that, for the most part, Europeans weren’t trying to use disease as a means of clearing Indians off the land.

But not innocent inasmuch as there is a moral dimension to the invasion that Europeans carried out in the Americas. No Indians would have died of European diseases if the Europeans had not come to the Americas. Unintended consequences are still consequences.

Mann does touch on such questions, but, for me, his consideration of these issues were buried in all of the stories and factoids and speculations.

Again, what do I know? Many reviewers have praised the book, and many readers have purchased copies.

I wonder, though, after being entertained by Mann’s stories, how many readers, say, three months after reading the book, remember the details of any of them.

Patrick T. Reardon

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Hi Pat. I read this book soon after it was published. To me, it did read like a collection of separate magazine articles. It was the information given, which you have summarized, that I found interesting and memorable, not the overall reading experience. I think I would have the same experience if I attended a university lecture on this material. I just found the subject matter so interesting that the packaging and narrative delivery became a secondary concern.

Hey, Darnell — Great to hear from you. This is our History Book Club book for this month. We’re meeting on Tuesday in Oak Park if you’d like to join us. (Let me know.) You’re right, the material is all very interesting and eye-opening. My complaint is from the standpoint of a reader and a writer. For me, there were so many dates, places, anecdotes, academic controversies, bad old theories, good new theories and so on that my eyes glazed over and I found I had a hard time retaining anything except the main bullet points. The writer in me was frustrated at this, realizing that there were any number of other ways of writing the book that wouldn’t have had to have this “glazed-over” problem. Still, I’m sure that, on Tuesday, I’ll be in the minority in the discussion since this book really does open a window onto stuff most of us don’t know much or anything about…..or, worse, think we know stuff that’s actually wrong! Hope you’re doing well. Pat

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

© Copyright 2024 | Patrick T Reardon.Com | All Rights Reserved

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus-Book Review

How I chose this book for our South America to the World book club is by what I like to call the result of a book chain effect. When you read a good book, certain authors get mentioned, and curiosity takes its course. Especially in specific topics that you desire to understand better or learn more about it. Our December’s book review “Long Road From Quito: Transforming Healthcare in Rural Latin America” by Tony Hiss led me to Mr. Mann’s book on the Americas.

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Shines a new light on everything we thought we knew about the Americas, and its habitants. It is a book full of new information got by professionals on various fields. Historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, ecologists, geographers, epigraphers, and linguists alike. All contributed to the new results used in the book.

Mr. Mann’s cites “Demography, climatology, epidemiology, economics, botany, palynology (pollen analysis); molecular and evolutionary biology; carbon-14 dating, ice-core sampling, satellite photography, and soils assays; genetic microsatellite analysis and virtual 3-D fly-throughs—a torrent of novel perspectives and techniques cascaded into use.” We are left with new knowledge and amazement of previous civilizations.

1491 book explains the advance in scientific research done in the matter. Shifting our pre-conceived ideas, and what we were taught in high school and universities. Mr. Charles C. Mann compiled all this new information in the most extraordinary way. Science plays the main role in all new discoveries presented in the book.

Once again authors make the remark that all we know about older civilizations is based on European chronicles. Mr. Mann established this fact in his book, as Mr. MacQuarrie mentioned in his book our July’s book review “The Last Days of the Incas.” We can agree that it is bias account.

1491 book contains three parts in which the author explains to be Indian demography (Part I), Indian origins (Part II), and Indian ecology (Part III) plus coda. It is an ample read. I praise the author for presenting us new historical information in the most engaging and entertaining way. Never a dull part in the book, and it is easy to understand. I have definitely learned a lot from it, which is the most rewarding effect on spending time and money on something.

As I have stated before, a book that starts with a map is a good start, especially in such topic like this. The author presents a map of Native America as it could have been in 1491.

As a Peruvian-American, I am fascinated by what scientists are discovering now. As well as to have a better understanding of what they found before. The author shares a more complete account on the first colonists’ (pilgrims) arrival to North America. There is a more comprehensive narration of what took place on the First Thanksgiving. The influence that Native Americans had on the visitors and so on.

Scientists are coming closer to discovering one of the biggest mysteries of our time. Why or how ancient populations disappear? The Maya culture comes to mind. Also, how was possible for the Spaniards with only over one-hundred men to conquer the Incas? We know the Incas had a bigger army and possessed great military skills; well planned strategies showed by the conquers themselves performed.

This reminds me of our visit to Mesa Verde, to what I refer as, The Machu Picchu of North America. Where we were told the Anasazi people just disappear. There are speculations about it, but this book gives me an idea of what might have happened.

I have a better understanding now of The Three Sisters (maize, beans, and squash) the most efficient way to grow maize established by the Native Americans. Trade was another practice used by these indigenous groups.

The more I read about the history of the Incas, the more I am thrilled by it. To quote the author “In 1491, the Inka ruled the greatest empire on earth. Bigger than Ming Dynasty China, bigger than Ivan the Great’s expanding Russia, bigger than Songhay in the Sahel or powerful Great Zimbabwe in the West Africa tablelands, bigger than the cresting Ottoman Empire, bigger than the Triple Alliance, bigger by far than any European state, the Inka dominion extended over a staggering thirty-two degrees of latitude—as if a single power held sway from St. Petersburg to Cairo.” We have a better understanding now on how they worked. The genius of Pachacutec and his hegemonic empire. The Tawantinsuyo.

Scientist are deciphering the Quipus-Kipus (the ones that the Spaniards didn’t destroy) better now. This system of knots holds more information than previously thought. They now recognize the kipus as a written system. Author’s quote “All known writing systems use instruments to paint or inscribe on flat surfaces. Khipu are three-dimensional arrays of knots.” This, to me, is fascinating.

The author in his book refers to many cultures, among them the Olmec, the Maya, the Zapotec. And the Adena, and the Hopewell people. He mentioned how Native Americans used the land by burning it. Showing their agricultural skills. They were masters on working the land. Also, Mr. Mann explains the Maya’s calendar. Besides the use of the Christian calendar, they could add to it more. Author’s quote “The Mesoamerica calendar also tied together linear and cyclical time, but more elaborately.”

This book offers the most comprehensive history on Mesoamerica that I have read. All backed up with new data. Author’s quote “Tenochtitlan dazzled its invaders… Even more astounding that the great temples and immense banners and colorful promenades were the botanical gardens—none existed in Europe.” Unfortunately for us. The conquerors were the only ones who got to marvel Montezuma’s land in all its splendor. On the other hand, historians were able to find some old accounts on the subject.

On the south he talks about People of Norte Chico, Wari and Tiahuanacu, Chimu, Moche cultures. The Chinchorro and their mummies, the Sumerians. And many artifacts and ruins found. Using cotton in Peru, the Nazca lines , Chavin de Huantar , etc. Also, how Native Americas grew maize with their “millpa” system, and the used of potato by Andean farmers. He analysis how many cultures had influenced others, their trade systems and yes, the use of government.

Something that caught my attention was this, author’s quote “scientists did not confirm the existence of the Great Wall of Peru, a forty-mile stone rampart across the Andes, until the 1930s. And it still has never been fully excavated.” Thinking about it, we can assume that there is still so much to be discovered!

More and more, scientists are leaning toward epidemic diseases, introduced by Europeans. As the main cause of population decline in the Americas. The biggest of them all, smallpox affected the entire continent. It was devastating, for it exposed the susceptibility to the natives. If we add to these, conflict among cultures, and civil wars, the result was the most favorable for conquerors. Two great examples were Cortes, who conquered the Aztec empire. And Pizarro, who conquered the Incas.

1491 is a controversial book, and it will continue to be so. In part because of some old historians unwilling to accept new results and professional rivalry. The Americas in many respects remains to be a mystery. Thus, scientists are working on it, trying to interpret or decipher old artifacts becomes more extraordinary. We can’t avoid to give credit where credit is due. People from the Americas were more advanced than previously thought. They had great organization skills in government. Possessed military strategy, they were self-reliant; they had laws; they had impressive agricultural skills, built cities, and they were great astronomers.

This is a book that I would like to keep as a reference book, the amount of information provided is ample. Mr. Mann’s book is without a doubt a book that all interested in ancient civilizations must read.

– Yanira K. Wise, March, 2020

5 Best Ruins in Peru that are not Machu Picchu

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann

Long Road From Quito: Transforming Healthcare in Rural Latin America by Tony Hiss.

The Last Days of the Incas by Kim MacQuarrie

Peru 100 by James M. Wise

Do connect with us:

ResearchGate: James M. Wise

Author´s page: James M. Wise

Photography page: JamesM.Wise.com

Author´s page: Yanira K. Wise

South America seems to refuse to show its inexhaustible creative force.

Share this:

- Aji de Gallina a Classic Peruvian Recipe

- HUK. QORICANCHA-FIRST CHAPTER OF “CUZCO GOLD”

You May Also Like

September’s book review “The White Rock” by Hugh Thomson

MENDOZA – ARGENTINA

Weird Scenes from within the Rublo Chico mine

- About Attack of the Books!

- Index of Reviews

- Contact Attack of the Books!

Attack of the Books!

Attack of the Books

Review |1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann

I’ll be the first to admit that my interests in the historical have generally been Eurocentric, especially the Roman Republic and Empire. Recently, though, I found reason to pick up Charles C. Mann’s “1491,” and I have had a hard time putting it down since.

The children’s nursery rhyme reminds us that “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” Just this last week we’ve celebrated Thanksgiving and the mythologized first meal shared by “Pilgrims” and Native Americans in the early years of Captain John Smith’s Plymouth Colony in the 1620s. But what came before Europeans in the “New World” of North and South America? What was already here when they arrived? Was there much more than a few human sacrificing Aztecs (in South and Central America) and nomadic tribes in North America?

Quite the contrary, says Mann. Rather, he says, the land was full of people, developed into complex cultures and polities. For example, and he expands on many, the Maya controlled an empire that was larger than any in the old world, both in size and population. The Mexica (pronounced Meh-shi-ka) had a literary culture full of metaphor and simile, and a rhetorical tradition that enabled them to meet Franciscan friars sent to convert them on equal ground. In North America, as far as the shores of New England, the coast was full hundreds of thousands of Native Americans–the nations of the Micmac, Passamoquoddy, Abenaki, Mahican, and the Massachusett, among others.

Indeed, there were so many people in both North and South America that Mann wonders if settlement by European colonists would have been possible but for the effects of disease on the native population. So devastating were diseases such as small pox, influenza, and non-sexually transmitted hepatitis that civilizations such as the Maya may have been destroyed before Europeans even landed on the shores of South America. Similarly, the nations of New England, which had filled the land and had traded with early French and English merchants during the 16th century, almost disappeared over a period as short as two to five years.

Why was disease so devastating? While not the central focus of the book, or even the examination of “what was here before 1492,” Mann explains how the relatively limited genetic stock of Native Americans presented insufficient diversity for the native populations to survive the diseases that had been active in Europe and Africa for thousands of years. Native Americans were in no way inferior–they just came from fewer people and thus had less genetic diversity, had never faced diseases as the Europeans (and their pigs) carried and therefore fewer of them survived the introduction of the diseases to the American peoples. The result was that within a few years, entire nations and their cultures all but vanished from the Earth…leaving the appearance of a empty land with only a few roving tribes. Indeed, says Mann, the reason those tribes were roving may be because they had been cut down from populations levels necessary to support a stable and stationary settlement.

Among some of the other interesting tales and studies that Mann shares in his book is the story of Tisquantum, who we know as Squanto. His name, which he may have given himself, meant something along the lines of “wrath of God,” and Mann suggests that when he appeared in the Plymouth Colony, his intentions may not have been as benign as have been told to us in elementary school pageants. Born an original New Englander, he was kidnapped by Europeans as a souvenir and taken to Spain. Eventually, he ended up in England in the home of a rich merchant, again as an oddity to show to visitors. Learning English, he eventually convinced the merchant to send him back to America. However, in the time between his kidnapping and return, hepatitis ran rampant through his and the other nations living in what is not modern-day Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, wiping out his people and others. He returned to an empty land and was captured by a rival nation, who later used him and his ability to speak English to liaison with the Plymouth Colony. He, in return, may have tried to use the colonists as leverage to take over the rival nation.

1491 is a fascinating book, and a fascinating piece of history, covering a period of history that we may have spent less time examining than is merited given the size and scope of the civilizations that preceded European colonization of the Americas. Containing cities that dwarfed Rome in its greatest day and Paris and London at the time, the Americas in 1491 were, by Mann’s telling, a busy, populated and colorful place, and it deserves a place in our histories and archives alongside those of the other great civilizations of history.

Share the books:

Dan Burton lives in Millcreek, Utah, where he practices law by day and everything else by night. He reads about history, politics, science, medicine, and current events, as well as more serious genres such as science fiction and fantasy.

[…] It’s a fascinating book, and a valuable companion to Mann’s 1491. […]

Email Address

- Adult Fiction (103)

- Author Posts (13)

- Biography (2)

- Blog Post (76)

- Children's Fiction (10)

- Collection (7)

- Comic Books (2)

- Discworld (2)

- Dystopia – YA (3)

- Ender's Game (21)

- Fantasy – Adult (44)

- Fantasy – YA (22)

- Giveaway (3)

- History (17)

- Hugo Nominee (29)

- Nebula Nominee (4)

- Nonfiction (122)

- Picture Books (36)

- Politics (2)

- Science Fiction – Adult (115)

- Science Fiction -YA (18)

- Uncategorized (2)

- Utah (local) Authors (40)

- Young Adult Fiction (60)

- Short Review | A Republic, If You Can Keep It by Neil Gorsuch

- Recommendation | The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt

- Reflections on Night by Elie Weisel

- Book Review | The Book Thief by Marcus Zusak

- Happy birthday, Stephen Ambrose

“When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes.” -Erasmus

Recent Posts

- Short Review | A Republic, If You Can Keep It by Neil Gorsuch 2024-11-18

- Recommendation | The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt 2024-07-02

- Reflections on Night by Elie Weisel 2024-06-19

- Book Review | The Book Thief by Marcus Zusak 2024-04-24

- Happy birthday, Stephen Ambrose 2024-01-10

Return to top of page

Copyright © 2024 · Innov8tive Child Theme on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in

Review of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

by Charles C. Mann

One of my favourite passages to assign to my English classes is an excerpt from All Our Relations , by Tanya Talaga. In it, she says, “The New World, so to speak, was already an Old World.” I love this excerpt, the facts that Talaga shares as she grounds them in her own search for identity and relations, because it approaches issues of colonialism through a different lens from the one we often see in Canada. The story of colonization, when it is taught at all, is often very one-sided and Eurocentric. The suffering of Indigenous peoples, when it is framed that way at all, is presented in the context of technologically and even culturally superior Europeans overwhelming and eliminating the small groups of Indigenous people who lived here. In this way, Talaga explains, settlers maintain control over the narrative of colonization, even as they allow it to be adjusted to be tragic. In reality, Indigenous peoples had vibrant and populous civilizations on these continents long before Europeans arrived. That’s the topic Charles C. Mann covers in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus . In a series of detailed yet never too dense chapters, Mann helps us understand the complexity of life in the Americas before they were ever named that. Although likely outdated in parts by now, this book was still so illuminating and invigorating. I can’t speak for how interesting an Indigenous reader would find it, but as a white person, I have to say, I needed this knowledge.

Mann’s overall thesis is simple: what we learn in school doesn’t match with the actual, current state of archaeological/anthropological ideas of life in pre-Columbian America. The textbooks misrepresent colonization , yes, but they also misrepresent the state of this land before European colonization. In so doing, they perpetuate the white supremacist idea of terra nullius —that Europeans are justified in settling the land because it was basically empty and unused. In the past, archaeologists supported that viewpoint—partly because, you know, ethnocentric blindspots and racism and all that, but also because the archaeological record is fragmentary and often difficult to locate and interpret.

To that end, Mann devotes the first part of the book to exploring the question of how many people lived here prior to 1492. It’s a difficult question to answer with anything like accuracy, something he and his sources acknowledge. Mann is careful throughout this book to discuss conflicting theories, to point out when the science and history are far from settled, and to discuss when source material or calculations might be problematic. This is one of the strengths of 1491 : while Mann certainly has an agenda here, it’s one built on careful reference to evidence. At no point does one get the sense that Mann is selectively presenting evidence to convince us he’s right. Instead, what he tries to do is show us that there is plenty of evidence that undermines the conventional narratives we’ve grown up with.

Much of this part of the book focuses on the role of disease in decimating Indigenous populations. (Decimation in its most literal meaning of “1 in 10” is, of course, grossly inaccurate in this case.) Recent scholarship suggests that Indigenous populations were far larger than initially estimated because initial contacts with Europeans allowed diseases like smallpox to spread far and wide in advance of colonization. Hence, as settlers moved in to new areas, the people they saw were often already greatly reduced in number. This is an interesting idea and a reminder that, when we are creating hypotheses in science, especially science that intersects with historical accounts, we need to be careful to consider all the angles.

Now, one of the most obvious potential problems with this book is that Mann is a settler journalist. Again, he confronts this head-on. He acknowledges that it is problematic that so much research relies on colonial records and Western ways of knowledge-gathering. To his credit, he often quotes Indigenous scientists, scholars, and activists, especially when their points of view disagree with a loud view in the scientific arena. We need to work on decolonizing anthropology and archaeology as much as the other sciences. This book is almost 20 years old, and I would hope that now, in 2021, an Indigenous journalist would be the one who writes this type of book. All I can say is that Mann does his best given the limits of his positionality. On a similar note, this book is a survey. The cultures discussed within all deserve their own books—probably volumes upon volumes of their own books—and I would love to see those written by Indigenous scholars.

The second part of the book moves from quantity to quality. Mann examines new theories regarding both how Indigenous peoples populated the Americas as well as the types of civilizations they created. Mann discusses the more well-known cultures that were recognizable even to colonizers as a type of society (even if those colonizers didn’t want to call it civilization): the Inka, the Triple Alliance (aka the Mexica/Aztec), the Maya, etc. He mentions Cahokia, which I had heard about. But perhaps more interesting is how he connects many of these stories. He doesn’t just talk about the Maya or the Aztec: he gets into the details of the various cultures that rose and fell around these giants of history. In so doing, he establishes how these more well-known empires didn’t exist in vacuums but rather emerged from complex societies and fell back into different but still complex societies. The end result is a picture of the Americas that is so much busier than the stereotypes would have us believe.

The final part of 1491 pulls back from social structure to discuss instead infrastructure. Again, we have this stereotype that Indigenous peoples were primitive and lived in harmony and balance with nature. In some ways this is a “positive” stereotype that frames Indigenous people as superior to greedy, extractive Europeans. In other ways this is a “negative” stereotype that frames Indigenous people as inferior to technologically innovative Europeans. Either way, it’s a stereotype that harms Indigenous people. It’s true that Indigenous peoples lived off the land in a symbiotic way. But as Mann seeks to demonstrate, across both continents Indigenous nations were shaping the land for practical uses, including agriculture. Not all Indigenous cultures were primarily hunter/gatherer or foragers. Some practised complex agriculture, which resulted in far-flung trade routes as well.

It’s just so incredible to see everything laid out like this in a single volume! Some of it I had heard about, lots of it I hadn’t, and all of it in far more detail than I had encountered before. Sure, some of it is outdated by now, and even at the time of writing was speculative at best. Mann isn’t claiming that his work is the definitive history of pre-Columbian America. Rather, 1491 explores how archaeologists and anthropologists are finally beginning to listen to what Indigenous people have been saying all along: we were always here; we know where we used to live before Europeans came; we have lost much as a result of colonization. For me as a white person, reading this book helps me educate myself so I can speak more forcefully against modern-day colonialism.

I recommend this book to anyone who wants a semi-academic, very detailed survey of Indigenous civilizations prior to contact with Europeans. It’s not a perfect volume. Sometimes Mann’s organization of ideas could be improved; sometimes his writing becomes a little too effusive or poetical for me. But the ideas, the evidence, the meticulousness of the research? It’s all there, and it is laid out in such a way that if you steep yourself in it like I did, you’ll walk away so much better informed about this topic than school ever did.

I just hope I can pass it on to my students.

Share on the socials

Twitter Facebook

Let me know what you think

Enjoying my reviews?

Bastian's Book Reviews

(Mostly) speculative fiction book reviews.

- Graphic Novels

Monday, 18 March 2019

Review: 1491: the americas before columbus by charles c. mann.

No comments:

Post a Comment

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Oct 9, 2005 · 1491 New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. By Charles C. Mann. Illustrated. 462 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $30. ... 10 Best Books of 2024: The staff of The New York Times Book Review has ...

Aug 12, 2005 · 1491 NEW REVELATIONS OF THE AMERICAS BEFORE COLUMBUS. by Charles C. Mann ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 12, 2005 An excellent, and highly accessible, survey of America’s past: a worthy companion to Jake Page’s In the Hands of the Great...

Aug 9, 2005 · Whenever I read a book like Charles C. Mann’s 1491. New Revelations of the America Before Columbus, I find myself torn between the idea that it would be useful to make some kind of excerpt in order to keep track of the general ideas and remarkable details, and the urge to read on because it is so damn interesting. As a rule, being a man of a ...

Aug 1, 2005 · Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers! About This Guide The introduction, discussion questions, suggested reading list, and author biography that follow are intended to enhance your group’s conversation about 1491, Charles Mann’s compelling and wide-ranging look at the variety, density, and sophistication of the cultures in the Western Hemisphere before the ...

Jan 5, 2023 · Prior to publishing 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus in 2006, Charles C. Mann had co-authored a few books on science and technology. But he had specialized in writing magazine pieces on scientific subjects for such publications as Fortune, Smithsonian, Technology Review, Vanity Fair, Science, the Atlantic

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus is a 2005 non-fiction book by American author and science writer Charles C. Mann about the pre-Columbian Americas. It was the 2006 winner of the National Academies Communication Award for best creative work that helps the public's understanding of topics in science, engineering or medicine.

Mar 2, 2020 · Mr. Mann established this fact in his book, as Mr. MacQuarrie mentioned in his book our July’s book review “The Last Days of the Incas.” We can agree that it is bias account. 1491 book contains three parts in which the author explains to be Indian demography (Part I), Indian origins (Part II), and Indian ecology (Part III) plus coda.

Recently, though, I found reason to pick up Charles C. Mann’s “1491,” and I have had a hard time putting it down since. The children’s nursery rhyme reminds us that “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

May 19, 2021 · Review of the book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, by Charles C. Mann. Kara.Reviews, May 19, 2021, accessed December 03, 2024. https://kara.reviews/1491/ MLA 8 Babcock, Kara. Review of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus , by Charles C. Mann. Kara.Reviews , 19 May 2021, kara.reviews/1491/

1491 is a book trying to give an overview of current thinking about what America was like before Columbus arrived. In particular, what the people, cultures and human ways of living were like (though animals and nature get a bit of a mention, too). It's also a book that tends to have unimpressive covers, both in the US and the UK editions.