ACADEMIC MAKERS

- Privacy Policy

DEFINING THE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH PROBLEM AND IDENTIFYING RESEARCH GAP

🎯 DEFINING THE MANAGEMENT RESEARCH PROBLEM AND IDENTIFYING RESEARCH GAP

Q: What is the Importance of Defining the Management Research Problem? A: Defining the management research problem is crucial as it sets the direction and scope of the study, guiding the researcher’s efforts and ensuring clarity in objectives.

Q: How is the Management Research Problem Defined? A: The management research problem is typically formulated as a clear and concise statement that outlines the specific issue or question the research aims to address within the context of management theory or practice.

Q: What Are the Key Considerations in Defining the Management Research Problem? A:

- 🌟 Relevance: Ensuring that the research problem is relevant to current management challenges, organizational goals, or academic interests.

- 💼 Specificity: Formulating the problem statement in a precise and focused manner to avoid ambiguity and facilitate targeted investigation.

- 📈 Feasibility: Assessing the feasibility of addressing the research problem within practical constraints such as time, resources, and access to data.

- 🌐 Context: Considering the broader context, industry trends, theoretical frameworks, or empirical evidence relevant to the research problem.

Q: Why is Identifying the Research Gap Important? A: Identifying the research gap helps researchers situate their study within the existing body of knowledge, highlighting areas where further investigation is needed to advance understanding or address unanswered questions.

Q: How is the Research Gap Identified? A: The research gap is identified through a comprehensive review of existing literature, where researchers identify areas where knowledge is lacking, conflicting, or insufficient to fully address the research problem.

Q: What Are the Key Steps in Identifying the Research Gap? A:

- 📖 Literature Review: Conducting a systematic review of relevant literature to understand the current state of knowledge, theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and empirical findings.

- 📊 Gap Analysis: Analyzing existing research to identify areas where gaps or inconsistencies exist in theoretical understanding, empirical evidence, or practical applications.

- 📝 Critical Evaluation: Critically evaluating the strengths and limitations of existing studies, identifying opportunities for further investigation, innovation, or refinement of existing theories.

📚 CONCLUSION

Defining the management research problem and identifying the research gap are essential steps in conducting rigorous and impactful research in the field of management. By clearly defining the problem statement and situating their study within the broader context of existing knowledge, researchers can contribute to advancing theory, informing practice, and addressing critical challenges in management.

Keywords: Management Research Problem, Research Gap, Relevance, Specificity, Feasibility, Context, Literature Review, Gap Analysis, Critical Evaluation.

3 easy ways to identify the research gap

📊 MANAGEMENT RESEARCH PROCESS Q: What is the Management Research Process? A: The management research process refers to the systematic steps followed by researchers to conduct investigations, gather data, analyze findings,…

Q: What is Management Research? A: Management research involves systematic investigation and analysis of management-related issues to gain insights, inform decision-making, and contribute to knowledge in the field. Q: Why is…

📊 MANAGEMENT RESEARCH: AN OVERVIEW Q: What is Management Research? A: Management research involves systematic investigation and analysis of management-related issues to gain insights, inform decision-making, and contribute to knowledge in…

- PILOT TESTING 🛫 PILOT TESTING Q: What is Pilot Testing in Research? A: Pilot testing, also known as a pilot study or feasibility study, involves a small-scale trial run of research methods, instruments,…

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH PROCESS AND TOOLS 📊 QUALITATIVE RESEARCH PROCESS AND TOOLS Q: What is Qualitative Research? A: Qualitative research is a methodological approach used to explore and understand complex phenomena, contexts, and experiences from the perspectives…

- RESEARCH OBJECTIVES, QUESTIONS, AND HYPOTHESIS 🎯 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES, QUESTIONS, AND HYPOTHESIS Q: What are Research Objectives in Management Research? A: Research objectives in management research specify the goals and aims of the study, outlining what the…

- THE DATA PREPARATION PROCESS 📑 THE DATA PREPARATION PROCESS Q: What is the Data Preparation Process in Research? A: The data preparation process involves organizing, cleaning, and transforming raw data collected during a research study…

- CONTEMPORARY MANAGEMENT RESEARCH IN MARKETING, FINANCE, HR, AND OPERATIONS 📊 CONTEMPORARY MANAGEMENT RESEARCH IN MARKETING, FINANCE, HR, AND OPERATIONS Q: What is Contemporary Management Research? A: Contemporary management research refers to the study and exploration of current issues, trends, and…

- SELECTING A DATA ANALYSIS STRATEGY 📊 SELECTING A DATA ANALYSIS STRATEGY Q: What is Data Analysis Strategy in Research? A: Data analysis strategy refers to the systematic approach used by researchers to analyze and interpret data…

- FIELD WORK/DATA COLLECTION PROCESS 📊 FIELD WORK/DATA COLLECTION PROCESS Q: What is the Field Work/Data Collection Process? A: The field work/data collection process involves systematic procedures and activities for gathering primary data from real-world settings…

- REPORT PREPARATION AND PRESENTATION 📊 REPORT PREPARATION AND PRESENTATION Q: What is Report Preparation and Presentation? A: Report preparation and presentation involve organizing research findings, analyses, and conclusions into a coherent document or presentation format…

- QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN PROCESS 📋 QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN PROCESS Q: What is the Questionnaire Design Process? A: The questionnaire design process involves several sequential steps aimed at creating a structured instrument for collecting data from respondents…

- DATA COLLECTION TOOLS 📊 DATA COLLECTION TOOLS Q: What Are Data Collection Tools in Research? A: Data collection tools are instruments or techniques used to gather information from individuals, respondents, or sources to address…

- ARRANGEMENT OF DATA 📋 ARRANGEMENT OF DATA Q: What is Data Arrangement in Research? A: Data arrangement involves organizing, structuring, and preparing collected data for analysis and interpretation. It encompasses the process of transforming…

- ORAL AND WRITTEN REPORTS: IMPORTANCE, TYPES, AND FORMAT 📊 ORAL AND WRITTEN REPORTS: IMPORTANCE, TYPES, AND FORMAT Q: Why are Oral and Written Reports Important in Research? A: Oral and written reports are essential for disseminating research findings, insights,…

- RESEARCH DESIGN 📊 RESEARCH DESIGN Q: What is Research Design? A: Research design refers to the blueprint or plan that outlines the approach, methods, and procedures for conducting a research study. It encompasses…

Powered by Contextual Related Posts

- MANAGEMENT RESEARCH: AN OVERVIEW

- DEFINITION & IMPORTANCE OF MANAGEMENT RESEARCH

- THE RESEARCH PROCESS

- TYPES OF BUSINESS RESEARCH

- DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO RESEARCH

- RESEARCH DESIGN

- SAMPLING AND NON-SAMPLING ERRORS

- PROBABILITY AND NON-PROBABILITY SAMPLING TECHNIQUES

- SAMPLE VS CENSUS

- SAMPLING DESIGN AND PROCEDURES

- SOFTWARE FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

- PRIMARY SCALES OF MEASUREMENT: NOMINAL/ORDINAL/INTERVAL/RATIO SCALE

- DATA MEASUREMENT PLAN

- PRIMARY VERSUS SECONDARY DATA

- SAMPLE SIZE

- DATA COLLECTION TOOLS

- HYPOTHESIS TESTING PROCEDURE

- DATA ANALYSIS

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH PROCESS AND TOOLS

- GRAPHS & CROSS TABULATIONS

- FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTIONS

- SELECTING A DATA ANALYSIS STRATEGY

- THE DATA PREPARATION PROCESS

- APPLYING FOR RESEARCH PROJECTS: AGENCIES AND PROCEDURES

- CONTEMPORARY MANAGEMENT RESEARCH IN MARKETING, FINANCE, HR, AND OPERATIONS

- PLAGIARISM AND UNETHICAL PRACTICES: CHECKING

- ETHICS IN PUBLICATION AND REPORT WRITING

- ORAL AND WRITTEN REPORTS: IMPORTANCE, TYPES, AND FORMAT

- REPORT PREPARATION AND PRESENTATION

- BUSINESS ANALYTICS AND INFORMATION SYSTEM

- BUSINESS RESEARCH

- CERTIFICATION COURSES

- DIGITAL MARKETING

- EXAM PREPRATION

- FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

- FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING

- GENERAL INSURANCE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

- INTERVIEW PREPARATION

- IT ENABLED BANKING

- LIFE INSURANCE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

- MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING AND CONTROL

- MANAGEMENT ACCOUTING

- MARKETING OF BANKING AND INSURANCE SERVICES

- ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOUR

- Ph.D. COURSEWORK – MANAGEMENT

- STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

Angola Transparency

Political Finance Questions

Management Decision Problem vs. Research Problem

In the realm of business and management, the distinction between a management decision problem and a management research problem is crucial for effective problem-solving and decision-making. While both types of problems require attention and resolution, they differ in their nature, objectives, and approaches. This article delves into the key differences between these two problem types, providing examples to illustrate their distinct characteristics.

- A decision problem focuses on determining what action the decision maker needs to take.

- It is action-oriented and motivated by results rather than goals.

- Decision problems are concerned with the possible actions that can be taken to address a specific issue or achieve a desired outcome.

- Examples of decision problems include determining how to arrest the loss of market share or whether to segment the market differently.

Research Problem:

- A research problem, on the other hand, focuses on determining what information is needed and how it can be obtained effectively and efficiently.

- It is information-oriented and aims to identify the underlying causes of a problem.

- Research problems are concerned with gathering the necessary information to make informed decisions.

- Examples of research problems include determining the impact of online education on students’ learning abilities or investigating the correlation between variables.

Management Decision Problem

A management decision problem arises when a manager or decision-maker faces a situation that requires a choice among alternative courses of action. It is characterized by its focus on determining what action needs to be taken to address a specific issue or achieve a desired outcome. Decision problems are action-oriented and motivated by results rather than goals.

Key Features:

- Action-Oriented Decision problems are concerned with the possible actions that can be taken to address a specific issue or achieve a desired outcome.

- Results-Driven The primary objective of a decision problem is to identify the course of action that will yield the most favorable results.

- Limited Information Decision problems often involve limited information and time constraints, requiring managers to make decisions based on the available data.

A company experiencing a decline in market share faces a management decision problem. The decision-maker must determine the best course of action to arrest the loss of market share. Options may include adjusting pricing strategies, enhancing marketing campaigns, or exploring new market segments.

Management Research Problem

A management research problem, in contrast, is a situation where there is a lack of information or knowledge necessary for making an informed decision. It is characterized by its focus on determining what information is needed and how it can be obtained effectively and efficiently. Research problems are information-oriented and aim to identify the underlying causes of a problem.

- Information-Oriented Research problems are concerned with gathering the necessary information to make informed decisions.

- Exploratory Research problems often involve exploring new areas or investigating relationships between variables to gain a deeper understanding of a phenomenon.

- Data-Driven Research problems rely on collecting and analyzing data to uncover patterns, trends, and insights that can inform decision-making.

A company considering implementing a new training program for its employees faces a management research problem. The decision-maker needs to determine the impact of online education on students’ learning abilities. This involves conducting research to gather data on student performance, satisfaction, and engagement in online learning environments.

Management decision problems and management research problems are distinct yet interconnected aspects of business and management. Decision problems require action, while research problems require information. By understanding the differences between these two types of problems, managers can better allocate resources, prioritize efforts, and make informed decisions that lead to successful outcomes.

- Quora: How would you distinguish between a management decision problem and a management research problem?

- Professional Shiksha: Management Decision Problem & Marketing Research Problem

1. What is a management decision problem?

A management decision problem is a situation where a manager or decision-maker must choose among alternative courses of action to address a specific issue or achieve a desired outcome. It is action-oriented and focused on determining the best course of action.

2. What is a management research problem?

A management research problem is a situation where there is a lack of information or knowledge necessary for making an informed decision. It is information-oriented and focused on gathering the necessary data and insights to understand the underlying causes of a problem.

3. How are decision problems and research problems related?

Decision problems and research problems are interconnected. Research problems often arise from decision problems, as the lack of information or knowledge hinders effective decision-making. Conversely, the findings from research can inform and improve the decision-making process.

4. What are the key differences between decision problems and research problems?

Decision problems are action-oriented and focus on determining the best course of action, while research problems are information-oriented and focus on gathering data and insights. Decision problems are often driven by results, while research problems are driven by a desire to understand the underlying causes of a problem.

5. What are some examples of decision problems?

Examples of decision problems include determining how to increase sales, reduce costs, improve customer satisfaction, or enter a new market.

6. What are some examples of research problems?

Examples of research problems include investigating the impact of a new marketing campaign, analyzing customer behavior patterns, or studying the relationship between employee motivation and job performance.

7. How can managers distinguish between decision problems and research problems?

Managers can distinguish between decision problems and research problems by considering the nature of the issue at hand. If the issue requires immediate action and a choice among alternative courses of action, it is likely a decision problem. If the issue requires gathering information and understanding the underlying causes, it is likely a research problem.

8. Why is it important to distinguish between decision problems and research problems?

Distinguishing between decision problems and research problems is important because it allows managers to allocate resources and prioritize efforts effectively. Decision problems require a focus on action and implementation, while research problems require a focus on data collection and analysis. By understanding the differences between these two types of problems, managers can make informed choices about how to address them.

Related posts:

- What is a Research Plan for a Research Paper?

- Exploring the World of Management Decision Problems

- Ethical Research Practices: Upholding Integrity and Respect in Research

- Risk and Issue Logs in Project Management

- Ethics in Social Research: Significance and Implications

- Ethics in Research: Upholding Ethical Principles in Research Involving Human Beings

What is Research Problem? Components, Identifying, Formulating,

- Post last modified: 13 August 2023

- Reading time: 10 mins read

- Post category: Research Methodology

What is Research Problem?

A research problem refers to an area or issue that requires investigation, analysis, and resolution through a systematic and scientific approach. It is a specific question, gap, or challenge within a particular field of study that researchers aim to address through their research endeavors.

Table of Content

- 1 What is Research Problem?

- 2 Concept of a Research Problem

- 3 Need to Define a Research Problem

- 4 Conditions and Components of a Research Problem

- 5 Identifying a Research Problem

- 6 Formulating a Research Problem

Concept of a Research Problem

The first step in any research project is to identify the problem. When we specifically talk about research related to a business organisation, the first step is to identify the problem that is being faced by the concerned organisation. The researchers need to develop a concrete, unambiguous and easily comprehensible definition of the problem that requires research.

If the research problem is not well-defined, the research project may be affected. You may also consider defining research problem and carrying out literature review as the foundation on which the entire research process is based.

In general, a research problem refers to a problem that a researcher has witnessed or experienced in a theoretical or real-life situation and wants to develop a solution for the same. The research problem is only a problem statement and it does not describe how to do something. It must be remembered that a research problem is always related to some kind of management dilemma

Need to Define a Research Problem

The researchers must clearly define or formulate the research problem in order to represent a clear picture of what they wish to achieve through their research. When a researcher starts off his research with a well-formulated research problem, it becomes easier to carry out the research.

Some of the major reasons for which a research problem must be defined are:

- Select useful information for research

- Segregate useful information from irrelevant information

- Monitor the research progress

- Ensure research is centred around a problem

- What data should be collected?

- What data attributes are relevant and need to be analysed?

- What relationships should be investigated?

- Determine the structure of the study

- Ensure that the research is centred around the research problem only

Defining a research problem well helps the decision makers in getting good research results if right questions are asked. On the contrary, correct answer to a wrong question will lead to bad research results.

Conditions and Components of a Research Problem

Conditions necessary for the existence of a research problem are:

- Existence of a problem whose solution is not known currently

- Existence of an individual, group or organisation to which the given problem can be attributed

- Existence of at least two alternative courses of action that can be pursued by a researcher

- At least two feasible outcomes of the course of action and out of two outcomes, one outcome should be more preferable to the other

A research problem consists of certain specific components as follows:

- Manager/Decision-maker (individual/group/institution) and his/ her objectives The individual, group or an institution is the one who is facing the problem. At times, the different individuals or groups related to a problem do not agree with the problem statement as their objectives differ from one another. The decision makers must agree on a concrete and clearly worded problem statemen.

- Environment or context of the problem

- Nature of the problem

- Alternative courses of problem

- A set of consequences related to courses of action and the occurrence of events that are not under the control of the manager/decision maker

- A state of uncertainty for which a course of action is best

Identifying a Research Problem

Identifying a research problem is an important and time-consuming activity. Research problem identification involves understanding the given social problem that needs to be investigated in order to solve it. In most cases, the researchers usually identify a research problem by using their observation, knowledge, wisdom and skills. Identifying a research problem can be as simple as recognising the difficulties and problems in your workplace.

Certain other factors that are considered while identifying a research problem include:

- Potential research problems raised at the end of journal articles

- Large-scale reports and data records in the field may disclose the findings or facts based on data that require further investigation

- Personal interest of the researcher

- Knowledge and competence of the researcher

- Availability of resources such as large-scale data collection, time and finance

- Relative importance of different problems

- Practical utility of finding answers to a problem

- Data availability for a problem

Formulating a Research Problem

Formulating a research problem is usually done under the first step of research process, i.e., defining the research problem. Identification, clarification and formulation of a research problem is done using different steps as:

- Discover the Management Dilemma

- Define the Management Question

- Define the Research Question

- Refine the Research Question(s)

You have already studied why it is important to clarify a research question. The next step is to discover the management dilemma. The entire research process starts with a management dilemma. For instance, an organisation facing increasing number of customer complaints may want to carry out research.

At most times, the researchers state the management dilemma followed by developing questions which are then broken down into specific set of questions. Management dilemma, in most cases, is a symptom of the actual problem being faced by an organisation.

A few examples of management dilemma are low turnover, high attrition, high product defect rate, low quality, increasing costs, decreasing profits, low employee morale, high absenteeism, flexibility and remote work issues, use of technology, increasing market share of a competitor, decline in plant/production capacity, distribution of profit between dividends and retained earnings, etc.

If an organisation tracks its performance indicators on a regular basis, it is quite easy to identify the management dilemma. Now, the difficult task for a researcher to choose a particular management dilemma among the given set of management dilemmas.

Business Ethics

( Click on Topic to Read )

- What is Ethics?

- What is Business Ethics?

- Values, Norms, Beliefs and Standards in Business Ethics

- Indian Ethos in Management

- Ethical Issues in Marketing

- Ethical Issues in HRM

- Ethical Issues in IT

- Ethical Issues in Production and Operations Management

- Ethical Issues in Finance and Accounting

- What is Corporate Governance?

- What is Ownership Concentration?

- What is Ownership Composition?

- Types of Companies in India

- Internal Corporate Governance

- External Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance in India

- What is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)?

- What is Assessment of Risk?

- What is Risk Register?

- Risk Management Committee

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

- Theories of CSR

- Arguments Against CSR

- Business Case for CSR

- Importance of CSR in India

- Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Developing a CSR Strategy

- Implement CSR Commitments

- CSR Marketplace

- CSR at Workplace

- Environmental CSR

- CSR with Communities and in Supply Chain

- Community Interventions

- CSR Monitoring

- CSR Reporting

- Voluntary Codes in CSR

- What is Corporate Ethics?

Lean Six Sigma

- What is Six Sigma?

- What is Lean Six Sigma?

- Value and Waste in Lean Six Sigma

- Six Sigma Team

- MAIC Six Sigma

- Six Sigma in Supply Chains

- What is Binomial, Poisson, Normal Distribution?

- What is Sigma Level?

- What is DMAIC in Six Sigma?

- What is DMADV in Six Sigma?

- Six Sigma Project Charter

- Project Decomposition in Six Sigma

- Critical to Quality (CTQ) Six Sigma

- Process Mapping Six Sigma

- Flowchart and SIPOC

- Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility

- Statistical Diagram

- Lean Techniques for Optimisation Flow

- Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- What is Process Audits?

- Six Sigma Implementation at Ford

- IBM Uses Six Sigma to Drive Behaviour Change

- Research Methodology

- What is Research?

What is Hypothesis?

- Sampling Method

Research Methods

- Data Collection in Research

Methods of Collecting Data

- Application of Business Research

- Levels of Measurement

- What is Sampling?

- Hypothesis Testing

- Research Report

- What is Management?

- Planning in Management

- Decision Making in Management

- What is Controlling?

- What is Coordination?

- What is Staffing?

- Organization Structure

- What is Departmentation?

- Span of Control

- What is Authority?

- Centralization vs Decentralization

- Organizing in Management

- Schools of Management Thought

- Classical Management Approach

- Is Management an Art or Science?

- Who is a Manager?

Operations Research

- What is Operations Research?

- Operation Research Models

- Linear Programming

- Linear Programming Graphic Solution

- Linear Programming Simplex Method

- Linear Programming Artificial Variable Technique

- Duality in Linear Programming

- Transportation Problem Initial Basic Feasible Solution

- Transportation Problem Finding Optimal Solution

- Project Network Analysis with Critical Path Method

- Project Network Analysis Methods

- Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT)

- Simulation in Operation Research

- Replacement Models in Operation Research

Operation Management

- What is Strategy?

- What is Operations Strategy?

- Operations Competitive Dimensions

- Operations Strategy Formulation Process

- What is Strategic Fit?

- Strategic Design Process

- Focused Operations Strategy

- Corporate Level Strategy

- Expansion Strategies

- Stability Strategies

- Retrenchment Strategies

- Competitive Advantage

- Strategic Choice and Strategic Alternatives

- What is Production Process?

- What is Process Technology?

- What is Process Improvement?

- Strategic Capacity Management

- Production and Logistics Strategy

- Taxonomy of Supply Chain Strategies

- Factors Considered in Supply Chain Planning

- Operational and Strategic Issues in Global Logistics

- Logistics Outsourcing Strategy

- What is Supply Chain Mapping?

- Supply Chain Process Restructuring

- Points of Differentiation

- Re-engineering Improvement in SCM

- What is Supply Chain Drivers?

- Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model

- Customer Service and Cost Trade Off

- Internal and External Performance Measures

- Linking Supply Chain and Business Performance

- Netflix’s Niche Focused Strategy

- Disney and Pixar Merger

- Process Planning at Mcdonald’s

Service Operations Management

- What is Service?

- What is Service Operations Management?

- What is Service Design?

- Service Design Process

- Service Delivery

- What is Service Quality?

- Gap Model of Service Quality

- Juran Trilogy

- Service Performance Measurement

- Service Decoupling

- IT Service Operation

- Service Operations Management in Different Sector

Procurement Management

- What is Procurement Management?

- Procurement Negotiation

- Types of Requisition

- RFX in Procurement

- What is Purchasing Cycle?

- Vendor Managed Inventory

- Internal Conflict During Purchasing Operation

- Spend Analysis in Procurement

- Sourcing in Procurement

- Supplier Evaluation and Selection in Procurement

- Blacklisting of Suppliers in Procurement

- Total Cost of Ownership in Procurement

- Incoterms in Procurement

- Documents Used in International Procurement

- Transportation and Logistics Strategy

- What is Capital Equipment?

- Procurement Process of Capital Equipment

- Acquisition of Technology in Procurement

- What is E-Procurement?

- E-marketplace and Online Catalogues

- Fixed Price and Cost Reimbursement Contracts

- Contract Cancellation in Procurement

- Ethics in Procurement

- Legal Aspects of Procurement

- Global Sourcing in Procurement

- Intermediaries and Countertrade in Procurement

Strategic Management

- What is Strategic Management?

- What is Value Chain Analysis?

- Mission Statement

- Business Level Strategy

- What is SWOT Analysis?

- What is Competitive Advantage?

- What is Vision?

- What is Ansoff Matrix?

- Prahalad and Gary Hammel

- Strategic Management In Global Environment

- Competitor Analysis Framework

- Competitive Rivalry Analysis

- Competitive Dynamics

- What is Competitive Rivalry?

- Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy

- What is PESTLE Analysis?

- Fragmentation and Consolidation Of Industries

- What is Technology Life Cycle?

- What is Diversification Strategy?

- What is Corporate Restructuring Strategy?

- Resources and Capabilities of Organization

- Role of Leaders In Functional-Level Strategic Management

- Functional Structure In Functional Level Strategy Formulation

- Information And Control System

- What is Strategy Gap Analysis?

- Issues In Strategy Implementation

- Matrix Organizational Structure

- What is Strategic Management Process?

Supply Chain

- What is Supply Chain Management?

- Supply Chain Planning and Measuring Strategy Performance

- What is Warehousing?

- What is Packaging?

- What is Inventory Management?

- What is Material Handling?

- What is Order Picking?

- Receiving and Dispatch, Processes

- What is Warehouse Design?

- What is Warehousing Costs?

You Might Also Like

Data analysis in research, what is causal research advantages, disadvantages, how to perform, primary data and secondary data, what is measurement scales, types, criteria and developing measurement tools, cross-sectional and longitudinal research, what is parametric tests types: z-test, t-test, f-test, what is research types, purpose, characteristics, process, what is experiments variables, types, lab, field, what is questionnaire design characteristics, types, don’t, leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

World's Best Online Courses at One Place

We’ve spent the time in finding, so you can spend your time in learning

Digital Marketing

Personal growth.

Development

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

A research problem is the starting point of any study, as it defines the issue or challenge that the research intends to address. Clearly articulating a research problem is essential because it shapes the direction of the study, influencing research design, methodology, and analysis. This guide explores what a research problem is, the types of research problems, and how to develop one with clear examples to aid in understanding.

Research Problem

A research problem is a specific issue, difficulty, or gap in knowledge that prompts the need for investigation. It reflects the purpose of the research and the questions that the study aims to answer. Without a clear research problem, it is difficult to determine the scope, goals, and relevance of the research.

For example, in social sciences, a research problem might involve understanding factors that influence student motivation. In business, it could involve identifying reasons behind declining customer satisfaction.

Why is a Research Problem Important?

The research problem is the foundation of the research process because it:

- Defines the Study’s Purpose : It helps clarify what the research is trying to achieve.

- Guides the Research Design : It determines which methodologies and data collection techniques are suitable.

- Provides Focus and Direction : It prevents the study from being overly broad or unfocused.

- Establishes Relevance : A well-defined problem highlights the research’s significance and its contribution to knowledge.

Types of Research Problems

- Example : What are the psychological factors influencing digital addiction among young adults?

- Example : How can customer service training improve client retention in the hospitality industry?

- Example : How do rural and urban educational outcomes compare in terms of student performance?

- Example : What are the emerging behaviors associated with the use of augmented reality in retail shopping?

- Example : What are the common characteristics of high-performing teams in technology companies?

- Example : What effect does daily exercise have on reducing stress levels among college students?

Steps to Formulate a Research Problem

- Identify a Broad Topic Area Start by choosing a general area of interest. This could be anything from mental health and marketing to technology or education. Focusing on a topic you’re passionate about can make the research process more engaging.

- Conduct Preliminary Research Conducting initial research helps you understand existing knowledge and identify gaps. Look at recent studies, articles, or reports in your field to find areas that need further exploration.

- Narrow Down the Topic A broad topic needs to be narrowed to a specific issue. Consider the aspects of the topic that interest you most or that have limited research available. Narrowing the focus prevents the study from being too general and enhances its depth.

- Identify the Problem Clearly define the problem or gap that the research aims to address. Frame it as a statement that indicates the issue, its context, and its importance.

- Formulate Research Questions Develop research questions that provide a basis for investigating the problem. Good research questions are specific, clear, and feasible, guiding the research process and helping focus data collection.

- Assess Feasibility Evaluate if the research problem is manageable given available resources, time, and access to data. Feasibility ensures that the study is achievable and practical within constraints.

Examples of Research Problems

Example 1 : In Education

- Problem : Declining student engagement in online learning environments.

- Research Question : What factors contribute to decreased engagement in online courses compared to in-person learning?

Example 2 : In Business

- Problem : High employee turnover in customer service departments.

- Research Question : How does job satisfaction impact turnover rates among customer service employees?

Example 3 : In Healthcare

- Problem : Rising obesity rates among children in urban areas.

- Research Question : What are the primary lifestyle factors contributing to obesity among urban children?

Example 4 : In Psychology

- Problem : Increased rates of social media addiction among teenagers.

- Research Question : What psychological factors lead to social media addiction in teenagers?

Example 5 : In Environmental Studies

- Problem : Rapid decline in pollinator populations affecting crop yields.

- Research Question : What impact does pesticide usage have on pollinator populations in agricultural areas?

Tips for Defining a Strong Research Problem

- Make It Specific : Clearly state the issue you intend to investigate. Avoid overly broad topics that are difficult to address.

- Identify Relevance : Choose a problem that has practical, theoretical, or social importance, demonstrating why the study matters.

- Align with Research Goals : Ensure that the problem aligns with the overall objectives of your research or field of study.

- Keep It Manageable : Be realistic about what you can accomplish within your time frame, resources, and skills.

- Consider Originality : Aim to address a gap in the current literature, focusing on issues that have not been explored in depth.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Overly Broad Problems : A vague or broad problem can make it difficult to formulate research questions or collect relevant data.

- Irrelevant or Trivial Problems : Choose a problem that has value and contributes meaningfully to your field of study.

- Unfeasible Problems : Ensure that your research problem is practical and can be addressed with available resources.

- Confusing the Problem with the Method : Define the issue clearly instead of describing the method. For example, “Using interviews to study…” is a method, not a problem.

A well-defined research problem is crucial to successful research. By selecting a relevant, specific, and feasible problem, researchers set a strong foundation for their study. Whether you are studying education, business, psychology, or any other field, understanding the types and examples of research problems can help you structure a clear and focused investigation. Defining the problem carefully and creating focused research questions ultimately guides the research process, making your work impactful and meaningful.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Sage Publications.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach . Sage Publications.

- Kumar, R. (2019). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners . Sage Publications.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students . Pearson Education.

- Punch, K. F. (2014). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Subject index

Doing Management Research, provides answers to questions and problems which researchers invariably encounter when embarking on management research, be it quantitative or qualitative. This book guides the reader through the research process from beginning to end. An excellent tool for academics and students, that enables the reader to acquire and build upon empirical evidence, and to decide what tools to use to understand and describe what is being observed, and then, which methods of analysis to adopt. Additionally, there is an entire section dedicated to writing up and communicating the research findings. Written in an accessible and easy-to-use style, this book can be read from cover to cover or dipped into, to clarify particular issues during the research process. Doing Management Research results from “hands on” experience of a large group of researchers who have all had to address the different issues raised when undertaking management research. It is anchored in real methodological problems that researchers face in their work.

Constructing the Research Problem

- By: Florence Allard-Poesi & Christine Maréchal Christine Maréchal

- In: Doing Management Research

- Chapter DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781849208970.n2

- Subject: Business and Management

- Keywords: knowledge ; organizational effectiveness ; organizational learning ; organizations ; representation

- Show page numbers Hide page numbers

[Page 31] ‘What am I looking for?’ The research problem is the objective of a study – it is the general question the researcher is trying to answer. Inasmuch as it expresses and crystallizes the research's knowledge target, the subject of the inquiry is necessarily a key element in the whole research process. It provides guidelines by which researchers can question the aspects of reality they have decided to study, or can develop an understanding of the reality.

This chapter provides the researcher with some techniques to assist in elaborating the research problem. It begins by defining what is meant by a research problem, and shows how this signification can differ according to the investigator's epistemological assumptions. It then proposes different methods by which a research problem may be constructed, and presents a number of possible approaches to take. Finally, using examples, it illustrates the recursive nature of, and some of the difficulties involved in, the process of constructing the research problem.

The research problem is the general question the researcher is trying to respond to, or the objective of a study. In a way, it is the answer to the question ‘What am I looking for?’ The research problem is relatively broad and general, distinguishing it from other ‘questions’ that are in fact more precise and practical renderings of this essential objective. As this research objective is formulated as a question, it is clearly different from other research elements that do not necessarily involve a logic of inquiry: theoretical elements (concepts, models, theories), methodological elements (measurement tools, scales, management tools) or empirical elements (facts, events). Two examples of research problems are given below.

Example: Two research problems

1 Cossette and Audet (1992)

Working from a critical examination of the notion of representation in research into organizations, Cossette and Audet set out to ‘elaborate a method of mapping the representations held by managers within organizations.’

2 Allison (1971)

Allison's study was an attempt to understand how the United States government took the decision to blockade during the Cuban missile crisis.

The research problem is a key element of the research process: it translates and crystallizes the researcher's knowledge project, his or her objective. It is through the research problem that researchers study aspects of the reality they hope to discover, or attempt to develop an understanding of that reality.

To know what we are looking for seems to be a prerequisite for any research work. As Northrop (1959) puts it, ‘Science does not begin with facts or hypotheses but with a specific problem’. In accordance, a lot of textbooks assume that researchers always start from a defined problematic: a general question to which they want to respond. But the problems that we address as researchers are not simply handed to us by the world about us. We invent them, we construct them – whatever our knowledge goal may be. The process of constructing a research problem is then itself an integral part of the research process, a step that is all the more decisive as it constitutes the foundation on which everything else is to be built.

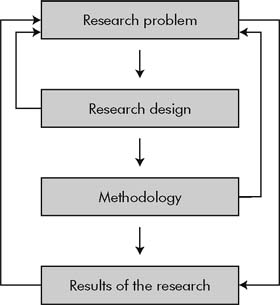

Traditionally, too, the processes of constructing the architecture and the methodology of a research project – the research design – are seen to be guided by the research problem. But these mapping-out stages can themselves influence the initial definition of the problematic at hand. They can lead to alterations in the research problem. In fact, it is not unusual for researchers to recognize that the concepts contained in their initial research problem are insufficient or poorly defined when they try to put them into practice, or after an in-depth reading of related works (see Figure 2.1).

Constructing the research problem is an essential step that can serve to guide the research process and the methodological choices made within it. At [Page 33] the same time, however, consideration of the research process and associated methodological choices can itself influence how the research problem will be constructed (see the following example for an illustration of this recursive aspect of constructing the research problem).

Figure 2.1 Construction of the research problem as an essential part of the research process

Constructing the research problem, a circular process

In her work into the cognitive approach of the organization, Allard-Poesi (1998) investigates causal mapping – the graphical representation of a person's causal beliefs about a particular domain. Her initial objective was to understand what a collective causal map in organizations actually is and how it emerges from the individual causal maps of its members, which supposedly vary greatly. A review of existent works on causal maps revealed that the notion of cognitive map is used in reference to very different methodologies, and involves differing and even contradictory constructs and visions of cognition. It seemed, in fact, more pertinent to consider a causal map as a tool for apprehending the representations held by members of an organization than as a theoretical construct in itself. This thinking led Allard-Poesi to redefine her question by way of the notion of representation. Her research problem became ‘What does collective representation in organizations consist of, and how does it emerge from the differing representations held by organizational members?’ By redefining her research problem in this way, Allard-Poesi was able to open up her theoretical framework, which had initially been centered on the cognitive approach of the organization. She was able to reconsider her research design, notably by taking a more socio-cognitive approach.

Constructing one's research problem appears then to be a recursive process, with no set rules. It is without doubt the moment in which the researcher's skills are really put to the test: skills in areas of intuition, precision, realism and imagination.

SECTION 1 WHAT IS A RESEARCH PROBLEM?

A Question Expressing a Knowledge Project

To construct a research problem is to elaborate a question or problematic through which the researcher will construct or discover reality. The question produced links or examines theoretical, methodological or empirical elements.

The theoretical elements of the research problem may be concepts (collective representation, change, learning, collective knowledge or cognitive schemes, for example), explicative or descriptive models of phenomena (for instance, innovation processes in an unstable environment or learning processes in groups) or theories (such as Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance). Some authors place particular emphasis on the primacy of the question's theoretical dimension. However, in our opinion, we can also construct a research problem by linking or examining theoretical elements, empirical elements or methodological elements. For example, empirical elements could be a decision taken by a board of directors, a result such as the performance of a business, or facts or events; methodological elements could include the method of cognitive mapping, [Page 34] a scale for measuring a concept or a method to support decision-making processes.

A theoretical, empirical or methodological element does not, in itself, constitute a research problem. To take up our first examples, neither ‘the Cuban missile crisis’ nor ‘a method of constructing the representations held by managers’ constitute in themselves a research problem. They are not questions through which we can construct or discover reality. However, examining these elements or the links between them can enable the creation or discovery of reality, and therefore does constitute a research problem. So, ‘How can we move beyond the limits of cognitive mapping to elicit the representations held by managers?’ or ‘How was the decision made to blockade during the Cuban crisis?’ do constitute research problems.

Examining facts, theoretical or methodological elements, or the links between them enables a researcher to discover or create other theoretical or methodological elements or even other facts. For instance, researchers may hope their work will encourage managers to reflect more about their vision of company strategy. In this case, they will design research that will create facts and arouse reactions that will modify social reality (Cossette and Audet, 1992). The question the researcher formulates therefore indirectly expresses the type of contribution the research will make: a contribution that is for the most part theoretical, methodological or empirical. In this way, we can talk of different types of research problem (see following examples).

Example: Different types of research problems

1 ‘What does a collective representation in an organization consist of, what is its nature and its constituent elements, and how does it emerge from the supposedly differing representations held by its members?’ This research problem principally links concepts, and may be considered as theoretical.

2 ‘How can we move beyond the limits of cognitive mapping in eliciting the representations held by managers?’ In this case, the research problem would be described as methodological.

3 ‘How can we accelerate the process of change in company X?’ The research problem here is empirical (the plans for change at X). The contribution may be both methodological (creating a tool to assist change) and empirical (speeding up change in company X).

The theoretical, methodological or empirical elements that are created or discovered by the researcher (and which constitute the research's major contribution) will enable reality to be explained, predicted, understood or changed. In this way the research will meet the ultimate goals of management science.

To sum up, constructing a research problem consists of formulating a question linking theoretical, empirical or methodological elements, a question which will enable the creation or discovery of other theoretical, empirical or methodological elements that will explain, predict, understand or change reality (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 How the research problem can link empirical, theoretical and methodological elements

Different Research Problems for Different Knowledge Goals

A knowledge goal assumes a different signification according to the researcher's epistemological assumptions. The type of knowledge researchers seek, and that of their research problem, will differ depending on whether they hold a positivist, interpretative or constructivist vision of reality.

For a positivist researcher, the research problem consists principally of examining facts so as to discover the underlying structure of reality. For an interpretative researcher, it is a matter of understanding a phenomenon from [Page 36] the inside in an effort to understand the significations people attach to reality, as well as their motivations and intentions. Finally, for constructivist researchers, constructing a research problem consists of elaborating a knowledge project which they will endeavor to satisfy by means of their research.

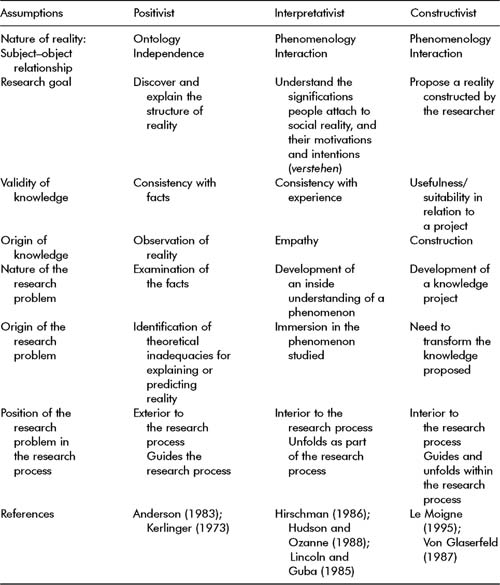

Table 2.1 Research problems and epistemological approach

These three different epistemological perspectives are based on different visions of reality and on the researcher's relationship with that reality. Consequently, they each attribute a different origin and role to the research problem, and give it a different position in the research process.

The research problem and, therefore, the process by which it is formulated will differ according to the type of knowledge a researcher wishes to produce. [Page 37] The relationship between the epistemological assumptions of the researcher and the type of research problem they will tend to produce is presented in Table 2.1. The categories presented here can only be indicative and theoretical. Their inclusion is intended to provide pointers that researchers can use in identifying their presuppositions, rather than to suggest they are essential considerations in the construction of a research problem. Most research problems in management sciences are in fact rooted in these different perspectives.

However, once a research problem has been temporarily defined during the research process, it is useful to try to understand the assumptions underlying it, in order to fully appreciate their implications for the research design and results.

A positivist approach

Positivists consider that reality has its own essence, independently of what individuals perceive – this is what we call an ontological hypothesis. Furthermore, this reality is governed by universal laws: real causes exist and causality is the rule of nature – the determinist hypothesis. To understand reality, we must then try to explain it, to discover the simple and systematic associations between variables underlying a phenomenon (Kerlinger, 1973).

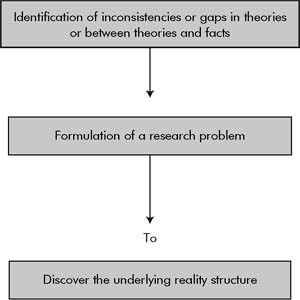

From the positivist viewpoint, then, the research problem consists essentially of examining facts. Researchers construct their research problem by identifying inadequacies or inconsistencies in existing theories, or between theories and facts (Landry, 1995). The results of the research will be aimed at resolving [Page 38] or correcting these inadequacies or inconsistencies so as to improve our knowledge about the underlying structure of reality (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Origins of the research problem and knowledge goal in the positivist research approach

The nature of the knowledge sought and of the research problem in the positivist epistemology imply that, in the research process, the research problem should be external to scientific activity. Ideally, the research problem is independent of the process that led the researcher to pose it. The research problem then serves as a guide to the elaboration of the architecture and methodology of the research.

An interpretativist approach

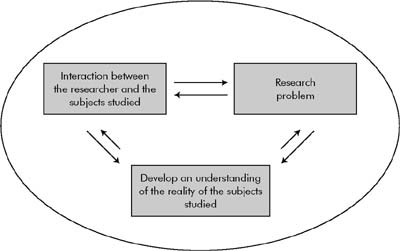

For interpretativists, reality is essentially mental and perceived – the phenomenological hypothesis – and the researcher and the subjects studied interact with each other – the hypothesis of interactivity (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988). In accordance with these hypotheses, interpretativists’ knowledge goal is not to discover reality and the laws underlying it, but to develop an understanding (verstehen) of social realities. This means developing an understanding of the culturally shared meanings, the intentions and motives of those involved in creating these social realities, and the context in which these constructions are taking place (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988; Schwandt, 1994).

In this perspective, the research process is not directed by an external knowledge goal (as in the positivist research approach), but consists of developing an understanding of the social reality experienced by the subjects of the study. The research problem, therefore, does not involve examining facts to discover their underlying structure, but understanding a phenomenon from the viewpoint of the individuals involved in its creation – in accordance with their own language, representations, motives and intentions (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988; Hirschman, 1986).

The research problem thus unfolds from researcher's immersion in the phenomenon he or she wishes to study (efforts to initiate change in a university, for example). By immersing him or herself in the context, the researcher will be able to develop an inside understanding of the social realities he or she studies. In particular, the researcher will recognize and grasp the participant's problems, motives and meanings (for instance, what meanings actors attach to the university president's efforts to initiate change, and how they react to them).

Here, constructing a research problem does not equate to elaborating a general theoretical problematic that will guide the research process, with the ultimate aim of explaining or predicting reality. The researcher begins from an interest in a phenomenon, and then decides to develop an inside understanding of it. The specific research problem emerges as this understanding develops. Although interpretativists may enter their research setting with some prior knowledge of it, and a general plan, they do not work from established guidelines or strict research protocols. They seek instead to constantly adapt to the changing environment, and to develop empathy for its members (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988). From the interpretative perspective, this is the only way to understand the social realities that people create and experience (Lincoln [Page 39] and Guba, 1985). The research problem will then take its final form semiconcomitantly with the outcome of the research, when researchers have developed an interpretation of the social reality they have observed or in which they have participated (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Origins of the research problem and knowledge goal in the interpretative research approach

This is, of course, a somewhat simplistic and extreme vision of interpretativism. Researchers often begin with a broadly defined research problem that will guide their observations (see Silverman, 1993, for example). This is, however, difficult to assess as most interpretative research, published in American journals at least, are presented in the standard academic format: The research problem is announced in the introduction to the article, and often positioned in relation to existing theories and debates, which can give the mistaken impression that the researchers have clearly defined their research problem before beginning their empirical investigation, as in the positivist approach.

A constructivist research approach

For the constructivists, knowledge and reality are created by the mind. There is no unique real world that pre-exists independently from human mental activity and language: all observation depends on its observer – including data, laws of nature and external objects (Segal, 1990: 21). In this perspective, ‘reality is pluralistic – i.e. it can be expressed by a different symbol and language system – but also plastic – i.e. it is shaped to fit the purposeful acts of intentional human agents’ (Schwandt, 1994: 125). The knowledge sought by constructivists is therefore contextual and relative, and above all instrumental and [Page 40] goal-oriented (Le Moigne, 1995). Constructivist researchers construct their own reality, starting from and drawing on their own experience in the context ‘in which they act’ (Von Glaserfeld, 1988: 30). The dynamics and the goal of the knowledge construction are always linked to the intentions and the motives of the researcher, who experiments, acts and seeks to know. Eventually, the knowledge constructed should serve the researcher's contingent goals: it must be operational. It will then be evaluated according to whether it has fulfilled the researcher's objectives or not – that is, according to a criterion of appropriateness (Le Moigne, 1995).

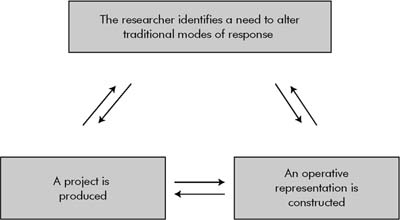

Figure 2.5 The constructivist research approach to the research problem

From this perspective, constructing the research problem is to design a goaloriented project. This project originates in the identification of a need to alter traditional responses to a given context – to change accepted modes of action or of thought. The construction of the research problem takes place gradually as the researcher develops his or her own experience of the research. The project is in fact continually redefined as the researcher interacts with the reality studied (Le Moigne, 1995). Because of this conjectural aspect of the constructivist process of constructing knowledge, the research problem only appears after the researcher has enacted a clear vision of the project and has stabilized his or her own construction of reality.

Thus, as in the interpretative research approach, the constructivist's research problem is only fully elaborated at the end of the research process. In the constructivist research approach, however, the process of constructing the research problem is guided by the researcher's initial knowledge project (see Figure 2.5). The researcher's subjectivity and purposefulness are then intrinsic to the constructivist project. This intentional dimension of the constructivist research approach departs from the interpretative one. The interpretative research process is not aimed at transforming reality and knowledge and does not take into account the goal-oriented nature of knowledge.

The type of research problem produced, and the process used to construct it, will vary depending on the nature of the knowledge sought and the underlying [Page 41] vision of reality. As we pointed out earlier, the categories we have presented are representative only. If a researcher does not strongly support a particular epistemological view from the outset, he or she could construct a research problem by working from different starting points. In such a process, it is unlikely that the researcher will follow a linear and pre-established dynamics.

SECTION 2 CONSTRUCTING THE RESEARCH PROBLEM

Point of departure.

Researchers can use different points of departure to elaborate their research problem. Concepts, theories, theoretical models relating to the phenomenon they wish to study, methodological approaches or tools, facts observed within organizations, a field-study opportunity, a general theme of interest, or a combination of these may be used. Studying a well-known research problem using a new methodological approach, using an existing theory to study a new phenomenon or re-examining theories (in light of the problems encountered by managers, for example) are all possible routes to take in elaborating a research problem.

Concepts, theories and theoretical models

Reading over published research works with a critical eye can reveal conceptual contradictions, gaps or inadequacies within the body of theoretical knowledge on a given subject. Strange constructs, theoretical inadequacies in some models, contradictory positions among researchers, heterogeneous research designs, concepts or study contexts, are all openings and, therefore, opportunities for constructing a research problem.

A large number of researchers have used the insufficiencies of existing theories (see the following example) or a comparison of two contradictory theoretical frameworks as starting points in constructing their research problems. In this connection, articles synthesizing the current state of a theme or a particular concept are often useful bases on which to construct a research problem.

Example: Starting from existing theories

Steers (1975) reviews 17 multivariate models of organizational effectiveness. Organizational effectiveness is defined as the efficiency with which an organization acquires and uses its resources within a given environment. The author compares these models along four dimensions: primary evaluation criteria, nature – descriptive versus normative – generalizability and derivation – and synthesizes their inadequacies. His analysis starts from the observation that the concept of organizational effectiveness is rarely defined in existent literature, even when it is expressly referred to. While the author does not himself explicitly choose a new perspective from which to study organizational effectiveness, his remarks and observations on the dimensions of the concept are still angles from which to elaborate new research problems.

[Page 42] For example, following on from Steer's work, one could think of introducing a social dimension in the concept of organizational effectiveness, a dimension that is often overshadowed in theoretical works. The research could thus aim to answer the following question: ‘What is the social dimension of organizational effectiveness?’

Detecting inadequacies or contradictions in theories or in definitions of existing concepts is one useful method for starting research. Using a theory or theoretical perspective to study phenomena other than those to which it has until now been applied can also form an interesting basis on which to elaborate research problems (see the following example). Finally, we can simply choose to test certain theoretical principles that have already been advanced, but have not yet been convincingly tested.

Example: Using an existing theoretical perspective to study a new phenomenon

Tracy (1993) proposed to use the living systems theory developed by Miller (1978) for studying organizational behavior and management. He focused his analysis on usual organizational topics and phenomena – in particular, organizational structure – to which the living systems theory has already been applied, and proposed a synthesis of this research. In this article, Tracy outlines the general precepts of the theory and then details its underlying assumptions and theoretical implications. The article offers a good introduction for those interested in constructing a research problem using this theoretical framework.

From Tracy's work, one could envisage studying organizational configurations using the living systems theory. This theory proposes in fact a typology of the subsystems involved in the organization of living systems, identifies the properties and the role of actors and suggests how to regulate the system transversally. The initial research question could be: ‘How can the specialization of skills be managed within organizations? ‘ The research goal would be to construct a typology of company configurations according to the organizational goals and environment – that is, using the living systems theory.

Starting from a methodology

While, at the moment, most research problems in management science seem to find their genesis in theoretical and conceptual thinking, the methodological approaches or tools used can also constitute interesting starting points for elaborating a research problem. Two possibilities are here available to the researcher. First, the research problem may consist of examining existing methods or methodological approaches, identifying their limits and attempting to propose new ones (see following example). One could propose a new scale for measuring performance, or a new method to analyze discourse, or to support decision-making, for example.

Example: Using a methodology

Eden et al. (1983) set out to design a method to support strategic decision-making in groups. Two assumptions underlie this research project: first, that creating consensus in a group while taking into account the particularities of its members’ [Page 43] individual visions is difficult and, second, that traditional group decision-making methods rely on formal approaches. The research goal, therefore, was to design a decision-making method that accounted for potential differences in managers’ representations of their problems, and that would facilitate consensus and creative resolution of strategic problems. The method they proposed used cognitive mapping techniques (see Chapter 16). Through cognitive mapping, managers’ representations are elicited and then aggregated. These aggregates are then discussed in groups, which enables the strategic problems encountered to be resolved creatively.

The other possible route is to use a new method or a new methodological approach to tackle a theoretical research problem that has already been the subject of other research. In this case, however, researchers should be careful to justify from the start the research problem they are studying (drawing on one of the configurations described in the previous section). Moreover, any method used implies a certain number of constraints that will, to a certain extent, limit the investigation. Many methods, for instance, fall within a given epistemological tradition or involve particular theoretical assumptions that are not necessarily made explicit. It is then very useful to pay attention to such considerations before deciding upon a particular research method. Researchers should weigh up all restraints inherent in the method used, and should evaluate their implications at a theoretical level.

Example: Tackling a classic research problem through a new method

Barr et al. (1992) began their research with the following question: ‘Why is it that, in the same environment, and whatever the quality and expertise of their management teams, certain companies are able to adapt and renew themselves while others cannot – and decline inexorably?’ Considering the limitations of classic theoretical frameworks, the authors chose to study the problem of organizational renewal from a cognitive perspective. They developed and analyzed organizational cognitive maps of two companies and then linked their conclusions to organizational learning theory.

Starting from a concrete problem

Companies’ difficulties and managers’ questions are favorite starting points for research in management. A research problem constructed on this basis ensures interest in the project from a managerial point of view. However, we need to make sure that, eventually, we also find a theoretical perspective on which the research problem and design will both rely.

Starting from a research setting

Some researchers begin their investigations with a research setting already in mind. This is very often the case when companies enter into research agreements: the researcher and the company agree on a relatively general research topic, for which precise modalities then have to be defined. In such a situation, [Page 44] the construction of a research problem will often be influenced by managerial considerations.

In the case of particularly inductive research, for example, when an interpretative approach is used (see Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991), researchers often start with a very broad question in mind and a research setting in which to carry out their enquiry. Their research problem will only truly emerge as they gain a clearer understanding of the context (see Section 1). There are, however, disadvantages in setting off on a field study without a specific research problem (see Section 2.2).

Starting from an area of interest

Finally, many researchers will naturally be drawn towards studying a particular theme. However, interest in a particular domain does not constitute a ‘question’ as such. The theme the researcher is interested in must then be refined, clarified and tested according to theories, methodologies, managerial interests or possible fieldwork opportunities, so as to elaborate a research problem as such. Researchers might look for any theoretical gaps in the chosen domain, review the concepts most frequently invoked and the methods most often used, or question whether other concepts or methods may be relevant; or identify managers’ preoccupations. Researchers have to consider what they can bring to the subject, and what field opportunities are available to them.

‘Good’ Research Problems

Beyond the various starting points mentioned previously, there are no recipes for defining a good research problem, nor any ‘ideal’ routes to take. On top of this, as we have seen, researchers subscribing to different epistemological paradigms will not define a ‘good research problem’ in the same way. We can, nevertheless, try to provide researchers with some useful guidelines, and warn them against possible pitfalls to be aware of when defining their research problem.

Delimiting the research problem

Be precise and be clear Researchers should always endeavor to give themselves as precise and concise a research problem as possible. In other words, the way the research problem is formulated should not lend itself to multiple interpretations (Quivy and Van Campenhoudt, 1988). For example, the question ‘What impact do organizational changes have on the everyday life of employees?’ is too vague. What are we to understand by ‘organizational changes’? Does this mean structural change? Changes in the company's strategy? Changes in the decision-making process? We would advise this researcher to put his or her [Page 45] research problem to a small group of people, and to invite them individually to indicate what they understand it to mean. The research problem will be all the more precise when interpretations of it converge and correspond to the author's intention.

Having a precise research problem does not mean, however, that the field of analysis involved is restricted. The problem may necessitate a vast amount of empirical or theoretical investigation. Having a precise research problem simply means that its formulation is univocal. In this perspective, researchers are advised to avoid problems that are too long or confused, which prevent a clear understanding of the researcher's objective and intention. In short, the research problem must be formulated sufficiently clearly to ground and direct the researcher's project.

Be feasible In the second place, novice researchers or researchers with limited time and resources should endeavor to give themselves a relatively narrow research problem:

If a research problem is too broad, researchers risk finding themselves with a mass of theoretical information or empirical data (if they have already started their fieldwork) which quickly becomes unmanageable and which will make defining the research problem even more difficult (‘What am I going to do with all that?’). In other words, the research problem must be realistic and feasible, i.e. in keeping with the researcher's resources in terms of personality, time and finances. This dimension is less problematic when researchers have significant time and human resources at their disposal (see Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991).

In short, a relatively limited and clear research problem prevents the researcher from falling into the trap of what Silverman (1993) calls ‘tourism’. Here, Silverman is referring to research that begins in the observational field, without any precisely defined goals, theories or hypotheses, and focuses on social events and activities that appear to be new and different. There is a danger here of overvaluing cultural or subcultural differences and forgetting the common points and similarities between the culture being studied and that to which one belongs. For instance, a researcher who is interested in managers’ work and restricts his or her attention to their more spectacular interventions would be forgetting aspects that are no less interesting and instructive – for example, the daily and routine aspects of the manager's work.

Be practical As their theoretical or empirical investigative work proceeds, researchers can clarify and narrow down their research problem. If they are initially interested in a particular domain (organizational learning for instance), they may formulate a fairly broad initial question (‘What variables favor [Page 46] organizational learning?’). They may then limit this question to a particular domain (‘What variables favor organizational learning during the strategic planning process?’) and/or specify the conceptual framework they are interested in (‘What cognitive or structural variables favor organizational learning during the strategic planning process?’). Through this narrowing down, the theoretical and empirical investigation will be guided and then easier to conduct.

Conversely, one should avoid confining oneself to a very narrow research problem. If the problem involves conditions that are too difficult to meet, the possibilities for empirical investigation may be greatly reduced. Similarly, if researchers focus too soon on a specific question, they may shut themselves off from many research opportunities that might well have broadened the scope of their research problem. They also risk limiting their understanding of the context in which the phenomenon studied is taking place. Finally, if researchers limit their research problem too much when it has been little studied, they may have only few theoretical and methodological elements to draw on when beginning their fieldwork. They will then have to carry out an exploratory theoretical work to redefine their initial research problem.

In sum, it appears difficult to strike a balance between a too large research problem that is impossible to contain, and a too limited research problem that shuts off study opportunities. This is one of the major difficulties researchers will confront when starting out on a research project.

Recognizing the assumptions underlying a research problem